The white beaked dolphin can be considered a very British species. Globally, it occurs only in the North Atlantic with particularly important populations in NW Europe (c. 16,500 estimated in July 2005), mainly in the North Sea, around Scotland, Iceland and southern Greenland. There is a small population that for many years has regularly visited Lyme Bay in south Devon, but in the rest of the English Channel and the Irish Sea, the species is rare.

The Scottish Government considered establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) for the white-beaked dolphin, but was unable to identify any discrete area with higher concentrations in Scottish waters. Marine Coastal Zones (MCZs) proposed in England were largely for sedentary species and not for whales and dolphins which were considered (rightly or wrongly) difficult to protect through this method.

The east coast of Britain has a number of locations visited by the species in summer. The Northumbrian coast is one of these. Here, Leanne Dixon interviews local GP, Ben Burville, about his observations of the species in the vicinity of the Farne Islands.

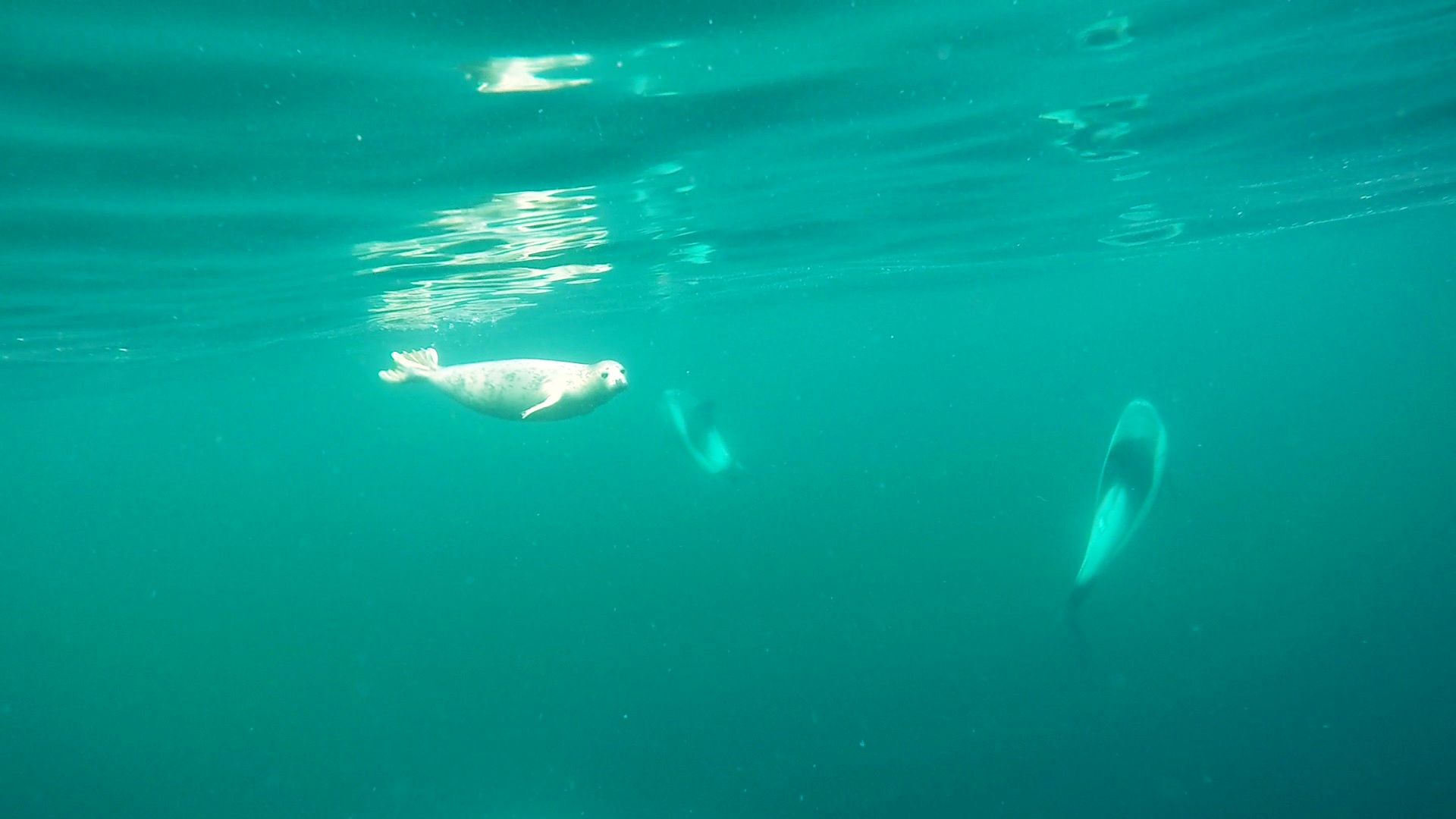

White-beaked dolphins underwater. Photo by Ben Burville.

White-beaked dolphins underwater. Photo by Ben Burville.

Ben Burville has a hobby like no other GP. He’s one of the driving forces of a study of White-beaked dolphins off the Northumberland coast, spending his hours beneath the waves. Sea Watch finds out the importance of his research in helping to protect this incredible species.

Sea Watch: You’re actually known as the ‘Seal Diver’, so how did you get involved in the study of White-Beaked Dolphins? What captures your interest most about this species?

Ben Burville: A producer from the BBC first called me “Seal Diver” and the name stuck. For over 16 years I have observed and recorded the underwater behaviour of grey seals around the UK coast. I have been fortunate to have filmed behaviour never seen before in grey seals, and have worked with the BBC, ITV, Sky and others on various programmes.

Ben (far right) & Alan Leatham (second right) with the Countryfile team

Ben (far right) & Alan Leatham (second right) with the Countryfile team

When I studied Oceanography and Biology at Southampton University my dissertation was on echolocation in bottlenose dolphins and I have always maintained an interest in cetaceans. In 2011, I was in discussion with a well-respected local boat operator William Shiel, his father-in-law John (an ex-herring fisherman with over 40 years of experience) and the skipper of Ocean Explorer, Alan Leatham. We discussed how in the past there had been sightings of “hundreds” of white-beaked dolphin off the Northumberland coast and in my mind I started to think about the possibility of a resident population. Having observed many dolphin species in the wild all over the world, white-beaked dolphin fascinate me as they are inquisitive and often exhibit spectacular jumps.

SW: The Marine Management Organisation granted you a special permit to enter the water with these creatures. What a privilege to join their underwater world! What do you most look forward to before a dive and do you have a particular favourite dive experience?

BB: I am very fortunate to have a scientific licence to film and observe this species underwater. I can honestly say that the experiences I have had to date with white-beaked dolphin in the water rank among some of the best memories of my life. There is something truly breathtaking when you are 18 miles offshore, snorkeling 10m underwater in sea 100m deep, face to face with a 3m long, 350kg dolphin who has chosen to approach you. It sometimes makes you wonder who is really observing who!

One of my favourite dives was last year when we were offshore and a pod of 5 white-beaked dolphins approached our boat. At the same time we spotted a young grey seal pup in the area just 20m away from the boat. Entering the water it was fascinating to see how one large male dolphin would swim near to the seal and how these two mammals interacted.

A young grey seal with white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

A young grey seal with white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

SW: The process of using underwater full body ID has proven much more effective for individual identification than dorsal fin photo ID in this species of dolphin. This in-water technique also further enables you to study ‘Tattoo Skin Disease’ in this species. How many white-beaked dolphins have you catalogued so far?

BB: Knowing that white-beaked dolphins are notoriously difficult to identify from dorsal fin photography, the underwater images (showing full body patterns) have proved invaluable. We have identified over 100 unique individuals to date. Tattoo Skin Disease is caused by pox virus (similar to the pox virus that causes Molluscum contagiosum in children). It may be a surrogate marker of pollution in certain cetaceans.

SW: It has been said that the proposed Marine Coastal Zones have neglected to include sites that would be beneficial in protecting cetaceans. You’ve been working with Newcastle University’s Marine Science department, collecting photos and underwater footage to further emphasise the need to protect the Northumberland coast. How far has your research come in terms of establishing this area as a key visiting site for White-Beaked Dolphins?

BB: We have without doubt identified a relatively small area off the Northumberland coast where there is proven “site fidelity” over a number of years (i.e. identified white-beaked dolphin have been “recaptured” on film in the same area over a year apart). With help from Dr Per Berggren and Matthew Sharpe from Newcastle University, along with Dr Marie-Francoise Van Bressem (one of the world’s leading experts of skin lesions in cetaceans) and Dr Koen Van Waerebeek we have had a scientific abstract approved for the European Cetacean Society meeting in Madeira in March. This abstract highlights the benefits from underwater images in the study of this species.

What I would like to do over the next year is survey this small area throughout the whole year with the aim of proving whether there is a resident Northumberland population of white-beaked dolphin. This, however, will require some funding as getting offshore to conduct this research is expensive.

Visible full body patterns in white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

Visible full body patterns in white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

SW: The main method of fishing in the North Sea is trawling, do you think the MCZs along the Northumberland coast can tackle the negative effects this method has on marine life? In your years as a diver, have you witnessed a change in the ocean environment first hand?

BB: Unfortunately, the Northumberland MCZs offer no real protection for dolphins or whales in the area. What many of the general public don’t realise is that the only obligation, once an MCZ has been approved, is to phase in management measures that are aimed to protect listed “features” within each MCZ. Highly mobile species, such as white-beaked dolphin, can only be listed as a “feature” of a MCZ if it can be proven that the dolphins use the waters within the MCZ for “key life stages” – such as mating or calving. This has not yet been proven in any of the approved MCZs so there is no obligation to implement management measures that would protect dolphins.

In the Farnes East MCZ, features do include things such as sea pens (sea pens are colonial marine cnidarians belonging to the order Pennatulacea, namely bottom dwelling soft corals) and sandy seabed areas where some flatfish and sandeels may be found. It would be hard to protect these without management measures to prevent bottom trawling (e.g. prawn fishing) so this may well be limited.

I have been diving for nearly 30 years and I have seen considerably less fish around coastal sites, more plastic waste and more discarded rubbish, like ropes, netting, and plastics.

SW: For you, what’s the most important thing about dedicating your time to the study and protection of marine life? What advice do you have for Sea Watch followers to support causes such as your own and protect our nation’s cetaceans?

BB: For me, time spent in and around the sea is very relaxing. Personally I believe that animals are far more intelligent than humans would like to admit and I have no doubt whatsoever that many marine mammals exhibit distinct personalities. We can learn a great deal about ourselves and our environment by studying marine mammals and wildlife in general.

Passengers on the Ocean Explorer in an encounter with white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

Passengers on the Ocean Explorer in an encounter with white-beaked dolphins. Photo by Ben Burville.

One key issue for me is that any observation must not disturb wildlife or adversely affect them in any way. As a rule I do not support invasive research methods. I also am keen to highlight that I never use any food or bait to attract marine life. I think that doing so alters behaviour and can even be dangerous. If any species chooses to interact with me it is entirely on the animal’s terms. Dr Denise Herzing has since 1985 been studying communication in free ranging Atlantic spotted dolphin in the Bahamas using in water techniques (The Wild Dolphin Projecthttp://www.wilddolphinproject.org/ ) with very interesting results.

I think for any Sea Watch followers my advice would be to learn as much as you can about the species you are observing and remember that by spreading the word you can help raise awareness of dolphins and whales around our coast. Many people will not even be aware that less than 45 minutes out of Seahouses harbour, Northumberland, their boat could be surrounded by white-beaked dolphins, choosing to bow ride. If people aren’t aware of this natural beauty on our doorstep, then the chance of protecting these beautiful animals is reduced.

A white-beaked dolphin seen from Ocean Explorer during Sea Watch Foundation’s

National Whale & Dolphin Watch 2015.

Photo by Alan Leatham.

A white-beaked dolphin seen from Ocean Explorer during Sea Watch Foundation’s

National Whale & Dolphin Watch 2015.

Photo by Alan Leatham.

To keep updated or get involved with Ben’s work, visit the team’s website at: www.northseapelagics.co.uk. Spread the word and keep supporting causes, such as this one, to protect our nation’s cetaceans!

By Leanne Dixon