Whales are not a taxon (a taxonomic category or group, such as a phylum, order, family, genus, or species), but an informal grouping of the infraorder Cetacea. This informal group encompasses a diverse group of marine mammals among which some of the longest-lived animals currently in existence.

The bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) is amongst the longest-lived mammals known to humankind. An Artic species, its average lifespan is estimated at more than 200 years.

Most whale species are similarly long-lived having life expectancies, which though shorter than the bowhead whale, are still considerably prolonged. The standard accepted average for most whales is actually similar to that of humans – falling somewhere in the 50-100 years’ range.

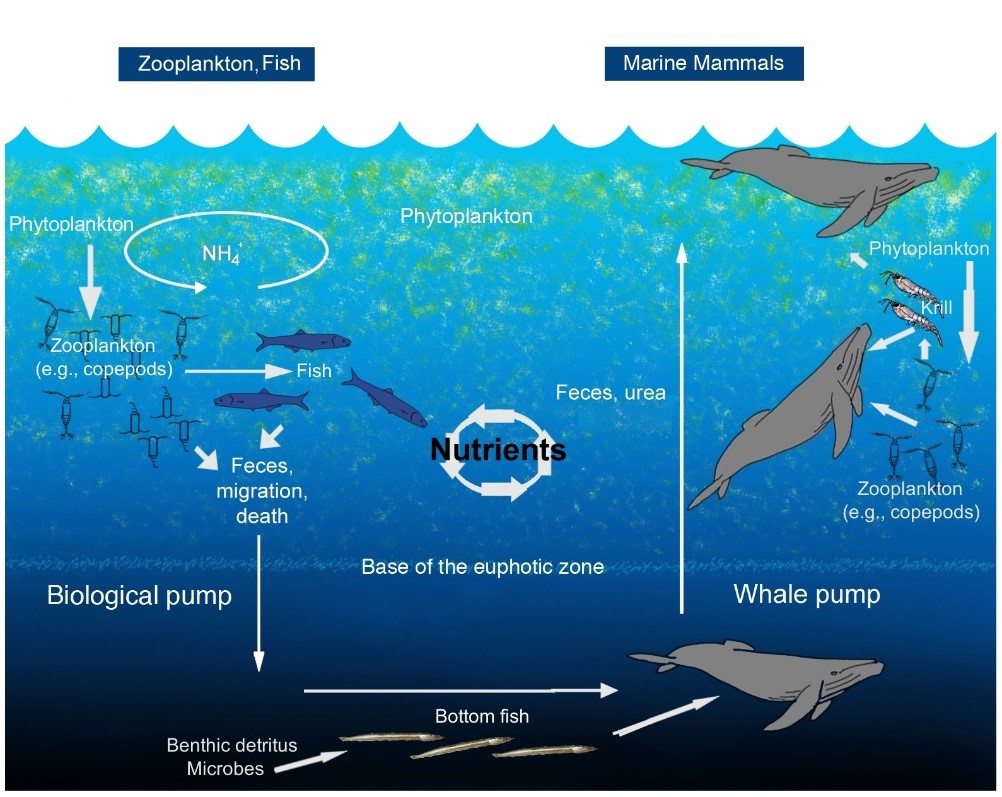

These long-lived aquatic goliaths play a particularly vital role in the marine ecosystem. From regulating global marine food webs to maintaining oceanic nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration, whales occupy an integral ecological niche and without them the ocean would be a vastly different habitat.

Remarkably, science suggests the dynamic exosystemic role whales play extends well past their natural life. This influence is best exemplified by the discovery of the first seabed whale fall during the 1970’s off the California coast.

A whale fall is an intermittent event which occurs when the carcass of a decomposing whale sinks, or “falls”, to the seafloor at a depth greater than 1000 metres. Once the carcass settles in this abyssal zone an entirely new ecosystem is born from its bones as the decaying flesh attracts organisms from miles around.

An illustration of the oceanic whale pump showing how whales cycle nutrients through the water column.

These localised benthic systems occur only at depth due to a unique combination of oceanic factors. Cold temperatures and high hydrostatic pressure slow decomposition and are essential to the onset of a successful whale fall. Carcass size is also of considerable influence as smaller cetaceans lack the mass necessary to sustain the complex communities which emerge around a fallen whale. A large cetacean can produce a whale fall capable of sustaining its own underwater community for decades.

Whale falls introduce organic matter, in mass, to an otherwise barren environment. This introduction allows for the emergences of specialised animal communities. Decomposition attracts varying species, many of whom take up permanent residence.

Whale fall communities change over time. As the whale moves from newly deceased to full decomposition over many years the composition of the residing animal communities also evolves. Initially, when the carcass still contains a large portion of flesh marine scavengers like sharks and hagfish will seek it out to feed on the soft tissue. This initial stage is followed by a secondary colonisation stage. The benthic sediment surrounding the skeleton becomes infused with organic matter during the decomposition process. This creates a habitat suitable to support populations of crustaceans and polychaetes for many years. Lastly, sulfophilic bacteria anaerobically breaks down the lipids embedded in the bones. This releases hydrogen sulphide which enables the growth of chemoautotrophic organisms (organisms that obtain energy through chemoautotrophy, the process of deriving energy through oxidizing inorganic chemical compounds, as opposed to photosynthesis). This final chemoautotrophic environment is capable of supporting other organisms such as mussels, clams, limpets, and sea snails for many years.

Written by Emily Rossi, Research Intern, 2017