Plastic pollution is a global issue, not only concerning our oceans and sea life, but the people that created it. Plastic was first created in the year 1862 by Alexander Parkes, and has been developed into a wide variety of products that we use on a day-to-day basis. Plastics are made up of synthetic material, e.g., nylon, that are then molded into shape, and are later used in paints, glues, packaging, technology, etc. Plastic production is influenced by the increase in anthropogenic activities, e.g., fishing, and has increased in production from two million tonnes in 1950 to 359 million tonnes in 2018. Unfortunately, all of this waste does not get properly managed, and ends up polluting and littering our oceans, and was first observed in the 1960s. This results in entanglement, ingestion and habitat degradation. This plastic waste eventually gets eroded to much smaller sizes, known as microplastics, typically sizing smaller than 5 mm. There are over 5 trillion plastic particles floating in the surface waters, unfortunately being ingested by marine organisms as they mistake it for their food. This includes the dolphins that we see around Cardigan Bay, but it also includes sea turtles, whale sharks, sea birds, zooplankton and many more.

Once entered into the water cycle, they break down and fragment into the smaller pieces. These small fragments carry chemicals such as PCBs (polybicarbonated biphenyl), DDTs (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and PBDEs (Polybrominated diphenyl ethers). These chemicals desorb into their biological tissue once ingested and cause health issues, such as oxidative and hepatic stress, induce immune response, alter membranes and cause alterations to gene expression. Their potential toxicity is dependent on the polymer type, size, shape and colour, which is why it is important to investigate what plastics these organisms are eating.

Filter feeders, e.g., baleen whales, whale sharks and manta rays, fill their mouths with the plastic-infested water to catch prey. Research shows that there are 6 times more plastic particles than there are zooplankton, ultimately leading to a lot of organisms consuming plastic. A study revealed that whale sharks consume approximately 171 plastic pieces daily, ranging from 15 to 200 mm, causing mortality for many individuals. Their stomach contents contained a lot of plastic packaging, see Figure 1, proving that the overuse of plastics in commercial and industrial use is a huge problem. For a lot of organisms, the consumption of plastics can also lead to starvation and other health issues. Manta rays have also been estimated to consume 63 pieces of plastic per hour, displayed in Figure 2, ranging from 5 to 94 mm. Another study found microplastics present in all 7 species of sea turtle, and only need to ingest one piece of plastic to end in mortality. A lot of these species are already threatened and are registered under the IUCN list, the increasing plastic problem will only make matters worse.

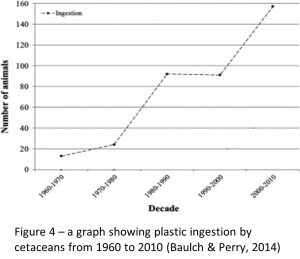

Cetacean strandings are thought to occur due to a number of factors and are primarily due to natural, environmental and anthropogenic causes. Naturally occurring factors could be that Marine mammals are considered as highly important sentinels for the effects that pollution have on the ocean and its organisms. These marine mammals include cetaceans, such as the bottlenose dolphin and grey seal that we see here in Cardigan Bay. Cetaceans (dolphins, whales and porpoises) are also a victim to plastic pollution, as over half of all species have ingested plastic. As seen in Figure 4, from 1960 to 2010, the rates have been rapidly increasing, showing no hope for this to be reduced. In a recent study, 50 specimens were tested for microplastics, 43 of which were cetaceans. The results confirmed that all 50 species contained microplastics, mostly retained in the stomach, with 84% of those microplastics being fibres, and the rest fragmented pieces. Marine mammals and other large marine species are at the top of the trophic level and tend to have a longer life span, so end up bioaccumulating chemical contaminants and plastic waste. Harbour porpoises that have been exposed to PCBs had shrunken testicles, suggesting an impact on their sperm count and fertility, and killer whales have damaged reproduction organs, leading to unsuccessful breeding. There is scientific proof that microplastics are passed through trophic levels, from zooplankton up to humans. Microplastics have also been found in sugar (44 particles per litre), bottled water (94.37 particles per litre) and seafood (1.48 particles per litre). Resulting in humans eating up to 5 grams of plastic a week, which is roughly the weight of a credit card.

What can be done and how can we help?

By understanding the impacts that plastic pollution bring, scientists can help to reduce mortality rates and improve their conservation rates. There are many ways to help reduce the amount of plastic that enters our oceans. This can be achieved through public education to the local communities that it effects, informing local governments and stakeholders, and NGOs (non-government organisations). NGOs such as 4Ocean, Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) and Marine Conservation Society (MCS) all promote the reduction in use of plastic and encourage cleaning projects. 4Ocean recovered more than 7 million pounds (lbs) of rubbish since 2017. SAS and MCS often organise beach clean-ups around the UK, by looking on their website, you can find one near you. In 2018, the SAS removed nearly 90,000 kg of rubbish and the MCS has also collected more than 11 million pieces of litter from beaches. The Ocean Cleanup have created passive systems that are estimated to remove over 50% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 5 years. Although there is still a lot left to be done to reduce the amount of plastic in our environment, there is some hope that we’ll be able to do it. You too can help by making some changes in your life, these include recycling, supporting schemes e.g., Ecobricks, litter picking, and growing your own food.

Rebecca Roberts Former Research Intern References 4Ocean. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://4ocean.com/?msclkid=b145f52ec7141cf51ec4a8c4538d1b45&utm_source=bing&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=%5BB%5DxRLSA%20Core%20-%20UK%20-%20Exact%20-%20Desktop&utm_term=4ocean&utm_content=4ocean (Accessed on 06/12/19). Baulch, S., & Perry, C. (2014). Evaluating the impacts of marine debris on cetaceans. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 80(1–2), 210–221. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.12.050 Fossi, M. C., Baini, M., Panti, C., Galli, M., Jiménez, B., Muñoz-Arnanz, J., … Ramírez-Macías, D. (2017). Are whale sharks exposed to persistent organic pollutants and plastic pollution in the Gulf of California (Mexico)? First ecotoxicological investigation using skin biopsies. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part C, 199, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2017.03.002 Germanov, E. S., Marshall, A. D., Mejder, L., Fossi, M. C., & Loneragan, N. R. (2018). Microplastics: No Small Problem for Filter-Feeding Megafauna. Science & Society, 33(4), 227–232. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.01.005 Meaza, I., Toyoda, J. H., & Wise, J. P. (2021). Microplastics in sea turtles, marine mammals and humans: a one environmental health perspective. Frontiers in environmental science, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.575614 Nelms, S. E., Barnett, J., Brownlow, A., Davison, N. J., Deaville, R., Galloway, T. S., Lindeque, P. K., Saltillo, D., & Godley, B. J. (2019). Microplastics in marine mammals stranded around the British coast: ubiquitous but transitory? Scientific Reports, 9(1075). Https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37428-3 Sampaio, C. L. S., Leite, L., Reis-Filho, J. A., Loiola, M., Miranda, R. J., de Anchieta C.C. Nunes, J., & Macena, B. C. L. (2018). New insights into whale shark Rhincodon typus diet in Brazil: an observation of ram filter-feeding on crab larvae and analysis of stomach contents from the first stranding in Bahia state. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 101(8), 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-018-0775-6 Sonam, C., Yadav, B. P., Siddiqui, N. A., and Chaturvedi, S. K. (2019). Mathematical modelling and analysis of plastic waste pollution and its impact on the ocean surface. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joes.2019.09.005 The results are in for this year’s Great British Beach Clean. (2019). Retrieved from Marine Conservation Society website: https://www.mcsuk.org/news/great-british-beach-clean-2019-report