Imogen is one of our Education and Awareness Assistants from our 2014 summer season who is here to talk about a different type of cetacean conservation – the care of display and research specimens in museums.

When you think of cetaceans, museums may not be the first place you think of to see them. With some species being so rarely seen in the wild, historical specimens in museums provide valuable resources, both for members of the public and scientific research. This is particularly true of Beaked Whales, as the majority of species spend their lives at great depths under the water, surfacing only briefly to breathe. This means spotting them can be a rare occurrence!

An example of this is the elusive Strapped Toothed Whale (Mesoplodon layardi). This species had only 140 recorded sightings before 1991, and the majority of these records were from animals stranding on the shore. The chance of encountering one of these amazing animals in the wild is very rare indeed! The males of this species develop impressive curved teeth that erupt from the lower jaw and curve around the upper jaw. In some cases these can reach up to 30 cm in length and even restrict how widely the animal can open its jaws to feed – a very strange adaptation. The position and shape of these erupted teeth have been used to help recognise and describe different species of Beaked Whale.

- Photo 1. Part of a Strapped Toothed Whale (Mesoplodon layardi) skull showing their impressive teeth. © University Museum of Zoology Cambridge

These erupted teeth are found in other species of male Mesoplodon Beaked Whales but in less extreme forms. In adult male Sowerby’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon bidens) the teeth erupt to form a triangular shape midway down the lower jaw. While this species is believed to be common, no one has been able to provide a reliable estimate of how many of these animals there are, since they are sighted so infrequently.

- Photo 2. A painted plaster cast of a Sowerby’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon bidens) skull before cleaning and repair. The triangular teeth can be seen midway down the lower jaw. © University Museum of Zoology Cambridge

Besides the Beaked Whales, another rarity can also be found at the Museum of Zoology in Cambridge – a double tusked Narwhal (Monodon monoceros). This Arctic dwelling species has only two teeth, usually embedded in the bone of the upper jaw, with the left tooth erupting in males to produce a long straight tusk.

- Photo 3. Underside of the top of a male Narwhal skull showing the smaller embedded tooth. © University Museum of Zoology Cambridge

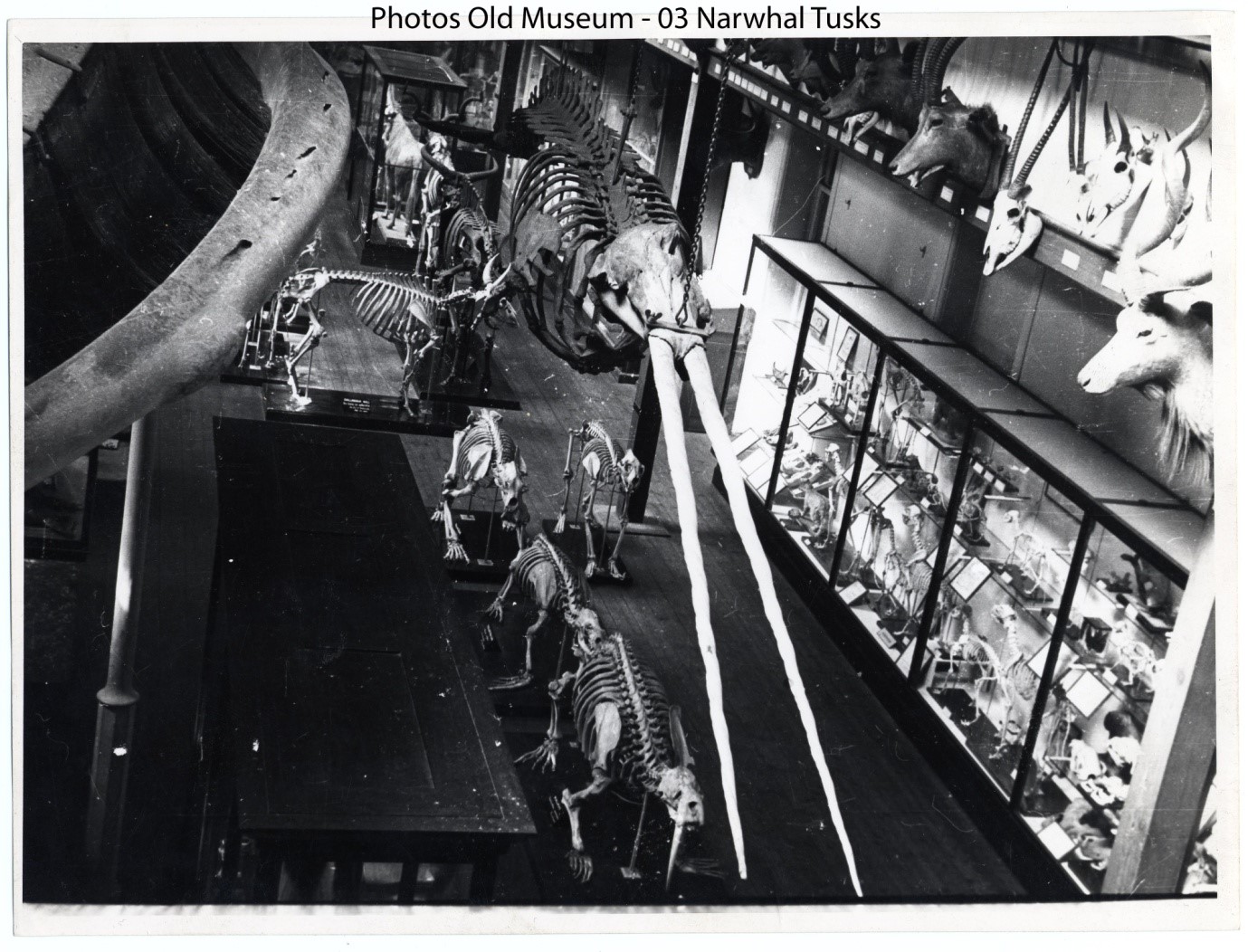

Very rarely the right tooth will also erupt, resulting in a double tusked Narwhal. An impressive complete skeleton of this rarity, collected in 1868, is on public display, suspended from the ceiling in the museum’s galleries.

- Photo 4. A rare double tusked Narwhal (Monodon monoceros) as displayed in the old museum layout. It now has a new home in the soon to be opened upper galleries. © University Museum of Zoology Cambridge

Preserving these skeletons gives researchers and the public an important insight into cetacean anatomy. Many visitors are surprised to see that the bones inside a dolphin’s or whale’s pectoral flipper are very similar in structure to our own hands.

One of the challenges of looking after historical cetacean specimens is keeping them clean and presentable. The naturally fat-rich content of cetacean bone means that oil seeps out over time. This causes bones to discolour to a yellowy-orange and encourages dust to cling to these surfaces, causing them to look dirty and potentially attracting damaging pests. Many of the skeletons at the Museum of Zoology are over 130 years old and few had been cleaned or properly conserved during that time. Treatment has to be gentle, so no long term damage is caused to these scientifically important skeletons, but effective too. Many of the skeletons have been carefully articulated, with their bones wired together, and these wires are checked to ensure that they haven’t corroded and need replacing. The large sheets of baleen in the huge mouth of the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) that dominates the Museum’s entrance hall also has to be checked regularly and treated against pest infestations. Everything we do to a museum specimen is carefully researched and documented so that the effects of any treatments carried out can be carefully monitored. All this work ensures that these skeletons will be around for visitors to marvel at and for researchers to use for many more years to come.

- Photo 5. A Short-beaked Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis) skeleton carefully removed from storage and photographed before treatment and going on public display. Oils leaching from the bones have discoloured the tail and pectoral flipper bones yellow. This specimen is unusual as the flesh around the flipper bones has been preserved along with the skeleton. © University Museum of Zoology Cambridge

Examples of the species mentioned and many others can be seen during a preview of the lower gallery of the University Museum of Zoology Cambridge until 10 June 2018. More cetacean skeletons, including the double tusked Narwhal, can be viewed in the public galleries after the full museum reopening on 23 June 2018. The museum is open from Tuesday to Sunday and entrance is free. Please see the website for further details.

Imogen Cavadino

Conservator at the Museum of Zoology, Cambridge