Orcinus orca, more commonly referred to as killer whale or orca, is the second most widely distributed mammal species in the world after humans and one of the most widely recognized species in the oceans. Orcas are distinctive because of their black and white coloration pattern with white eyepatches and gray saddle patches behind their dorsal fins. The contrasting coloration proves useful for coordinating group hunting activities and social signaling while also allowing orcas to be easily recognized in the ocean. Intelligent, long-lived, cooperative hunters, and intensely social animals, killer whales, or “wolves of the sea,” are the ocean’s top predator found in all the world’s oceans.1 Because of their generally large size, orcas are sometimes mistaken as whales. However, orcas are actually the largest member of the Delphinidae family living in tight social groups like other dolphin species. These orca groups, called pods, are stable family units with individuals generally remaining with their mothers for life. Observations of resident orca pods have confirmed they are led by matriarchs and scientists suggest this social structure occurs in other orca ecotypes.

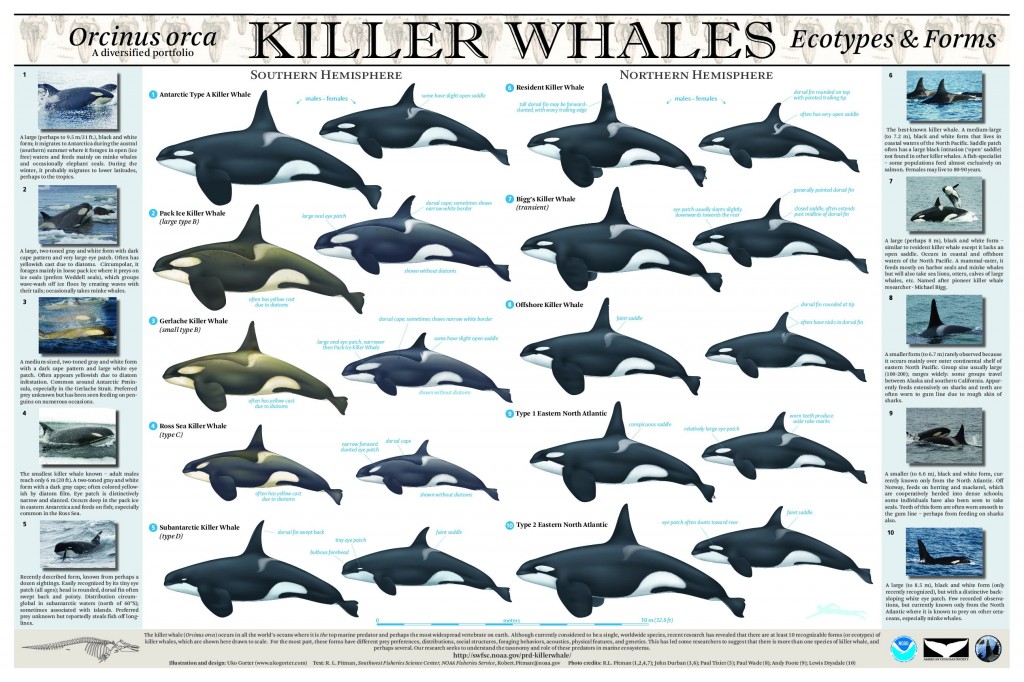

An ecotype is “a population of a species that survives as a distinct group through environmental selection and isolation and that is comparable with a taxonomic subspecies” (Merriam-Webster). There are ten orca ecotypes around the world. Scientists separated orca populations into these ten ecotypes based on body size, coloration, habitat range, vocalizations, diet, and social structure. Currently, all the orcas that populate the oceans are scientifically named Orcinus orca. However, scientists have advocated the need to separate some orca ecotypes into individual species.

Orca ecotypes – http://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedImages/Divisions/PRD/Programs/Ecology/Killer%20Whale%20Poster%20-%20final.jpg?n=1491

Orca ecotypes – http://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedImages/Divisions/PRD/Programs/Ecology/Killer%20Whale%20Poster%20-%20final.jpg?n=1491

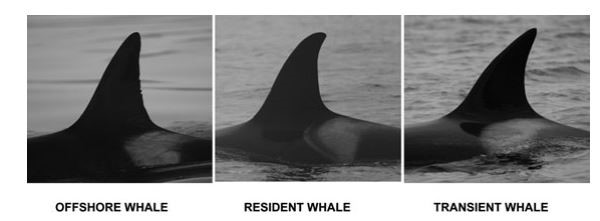

Resident, transient (Bigg’s), and offshore orca are the main ecotypes found in the North Pacific Ocean. Residents are physically distinguished by a dorsal fin that is rounded with a sharper angle at the rear corner and often open saddle patches2 feeding mainly on salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) with Chinook salmon being the most preferred species.3 Transients are physically distinguished by having pointed dorsal fins and large, uniformly gray saddle patches.4 These orca feed on a variety of marine mammals that include fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus), harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus), small cetaceans such as porpoises and dolphins, gray whales, and minke whales.3,5-8 Offshores are slightly smaller than both residents and transients with continuously rounded dorsal fins and closed saddle patches and specialize in feeing on Pacific sleeper sharks (Somniosus pacificus) and Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) resulting in extreme tooth wear.9-13

In the Southern Ocean, there are five orca ecotypes: Antarctic Type A, Pack ice Type B large form, Gerlache Type B small form, Ross Sea Type C, and Sub-Antarctic Type D.

Type A killer whales resemble the “typical” appearance of killer whales with black and white coloration with the largest of the Antarctic orcas having reported lengths of males up to 9 meters and 7.7 meters for females.14, 15 Orcas of this type have an eyepatch of medium size that is parallel to the body and lack a visible dorsal cape.14 Their distribution is around the entire Antarctic continent being sighted in mostly open water. Type A orcas are believed to feed primarily on Antarctic minke whales following minke whale migration from lower latitudes to Antarctic waters in the austral summer then north again in the autumn.14

Type B small and large forms have the similar coloration of two-tone gray and white along with a dark dorsal gray cape with paler gray side and flanks.14 Their eyepatches are oriented parallel to their bodies but are much larger compared to all other types of orcas .14 Some individuals become infested with diatoms on their bodies that turn white areas yellow and make gray areas appear brownish. The orcas are believed to make trips to tropical waters to shed the diatoms. The large, robust “pack ice” type B hunt among areas of ice and most prefer Weddell seals.16 They are known for cooperatively hunting by washing seals off ice floes.17 “Gerlache” orcas of the smaller type B form are about half the size of “pack ice” orcas. They forage in more open waters and choose to feed on penguins.16 Cookiecutter shark scars on both type B orcas indicate movements to both subtropical and tropical waters.18 Unlike type A, type B are observed in the pack ice during winter.

http://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedImages/Divisions/PRD/Programs/Ecology/Killer%20Whale%20Poster%20-%20final.jpg?n=1491

http://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedImages/Divisions/PRD/Programs/Ecology/Killer%20Whale%20Poster%20-%20final.jpg?n=1491

Ross Sea (Type C) orcas have a two-tone gray and white color pattern with dark gray dorsal capes and distinctive eyepatches that are narrow and tilted forward at about a 45° angle.14 They are the smallest type of orca only growing up six meters. Ross Sea orcas range around east Antarctic waters and are presumed to be fish eaters, Antarctic toothfish, Dissostichus mawsonii.19These orcas, like type B, also are believed to winter in the pack ice indicating that they stay close to Antarctica year-round but some have been photographed near New Zealand and Australia.14

Type D Subantarctic killer whales have extremely small eyepatches and more bulbous heads than other orca types with the typical black and white form of orcas.20 Sightings reported since 2004 between 40°S and 60°S suggest these orcas have a circumglobal and subantarctic distribution in the southern hemisphere.20 Groups sizes of type D orcas seen averaged about 17 individuals. Type D orcas are also suspected to feed on Patagonian toothfish near the Crozet Islands.21

Orca in the North Atlantic Ocean are suggested to be comprised of two sympatric, morphologically disparate types based on nitrogen stable isotope analysis and atypical tooth wear.22 Type 1 orcas grow to approximately 6.6 meters. Type 2 orcas grow to approximately 8.5 meters. Stable isotope analysis results indicated that type 1 orcas are generalists and have a varied diet of fish (herring & mackerel) or marine mammals (seals), while type 2 orca diets are suggested to be highly specialized to other cetaceans. Type 1 orcas seemed to have significantly more tooth decay than type 2 orcas indicative of different diets.2

In the waters surrounding Iceland, over 400 orca have been identified through photo-identification.23 These orca are Type 1 and mainly consume Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus).23 A population of Type 1 orca are also found in Norwegian waters numbering close to 900 individuals.24 The main prey item is Atlantic herring, but the orca also consume Atlantic mackerel, Atlantic salmon, harbor porpoises and seals.24

The Sea Watch Foundation contributes to studying orca in the waters of the United Kingdom by recording sightings from the public and promoting the annual Orca Watch during the last week of May in the Pentland Firth, Scotland. Orca Watch, started by Sea Watch Regional Coordinator Colin Bird, serves to study orca migrating south from Norway, Iceland and the Faroes. This yearly Orca Watch aids scientists studying these orca by contributing data on habitat ranges, population dynamics, and diet.

http://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedImages/Divisions/PRD/Programs/Ecology/Killer%20Whale%20Poster%20-%20final.jpg?n=1491

Overall, some populations have been studied more than others; however we still have much to learn about this extraordinary species and potentially multiple species. Additional orca populations are found in New Zealand, Hawaii, Canadian Arctic, Australia, Patagonia, Prince Edward Islands, Galapagos Islands, Falkland Islands and the Northern Indian Ocean with unique diets and social structures. Continued research is needed to better understand lesser known populations, yearly habitat ranges, genetic similarities and/or differentiation, toxicant concentration effects, acoustic characterization, human noise pollution effects, and climate change impacts.

Written by Stephanie Shaw Holbert, Research Intern, 2017

References

1Forney, K. A., and P. R. Wade. (2006). Worldwide distribution and abundance of killer whales.

In: Whales, Whaling and Ocean Ecosystems. J. A. Estes, D. P. DeMaster, D. F. Doak, T.,

M. Williams and R. L. Brownell. University of California Press, Berkeley. pp 145-162.

2Bigg, M. A., I. MacAskie and G. M. Ellis. (1983). Photo-identification of individual killer

whales. Whalewatcher 17:3-5.

3Ford, J. K., Ellis, G. M., Barrett-Lennard, L. G., Morton, A. B., Palm, R. S., & Balcomb III, K. C.

(1998). Dietary specialization in two sympatric populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in

coastal British Columbia and adjacent waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 76(8), 1456-1471.

4Ford, J. K. B., Ellis, G. M., & Nichol, L. M. (1992). Killer whales of the Queen Charlotte Islands: a

preliminary study of the abundance, distribution and population identity of Orcinus orca in

the waters of Haida Gwaii. Prepared for South Moresby/Gwaii Haanas National Park

Reserve, Canadian Parks Service. Vancouver Aquarium, Vancouver. British Columbia.

5Saulitis, E. L., C. O. Matkin, L. G. Barrett-Lennard, K. Heise and G. M. Ellis. (2000).

Foraging strategies of sympatric killer whale (Orcinus orca) populations in Prince William

Sound, Alaska. Marine Mammal Science 16:94-109.

6Heise, K., Barrett-Lennard, L. G., Saulitis, E., Matkin, C., & Bain, D. (2003). Examining the evidence

for killer whale predation on Steller sea lions in British Columbia and Alaska.

Aquatic Mammals, 29(3), 325-334.

7Jefferson, T. A., Stacey, P. J., and Baird R. W. (1991). A review of killer whale interactions with other

Marine mammals; predation to co-existence. Mamm. Rev 21: 151-180.

8Mizroch, S. A., & Rice, D. W. (2006). Have North Pacific killer whales switched prey species in

response to depletion of the great whale populations?. Marine Ecology Progress Series.

310, 235-246.

9Jones, I. M. (2006). A northeast Pacific offshore killer whale (Orcinus orca) feeding on a

Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis). Marine Mammal Science, 22(1), 198-200.

10Krahn, Margaret M., David P. Herman, Craig O. Matkin, John W. Durban, Lance Barrett-Lennard,

Douglas G. Burrows, Marilyn E. Dahlheim, Nancy Black, Richard G. LeDuc, and Paul R. Wade.

(2007). “Use of chemical tracers in assessing the diet and foraging regions of eastern

North Pacific killer whales.” Marine Environmental Research 63, no. 2: 91-114.

11Dahlheim, M. E., A. Schulman-Janiger, N. Black, R. Ternullo, D. K. Ellifrit and

K. C. Balcomb, III. (2008). Eastern temperate North Pacific offshore killer whales

(Orcinus orca): occurrence, movements, and insights into feeding ecology.

Marine Mammal Science 24:719-729.

12Ford, J. K. B. and Ellis, G. M. (2012). You are what you eat: foraging specializations and their influence

on the social organization and behavior of killer whales. In: Yamagiwa J., Karczmarski, L., eds.

Primates and cetaceans: field studies and conservation of complex mammalian societies.

New York: Springer, in press.

13Ford, J. K. B., G. M. Ellis, C. O. Matkin, M. H. Wetklo, L. G. Barrett-Lennard and R. E. Withler.

(2011). Shark predation and tooth wear in a population of northeastern Pacific killer whales.

Aquatic Biology 11:213-224.

14Pitman, R. L., and P. Ensor. (2003). Three forms of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters.

Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 5:131-139.

15Mikhalev, Y. A., M. V. Ivashin, V. P. Savusin and F. E. Zelenaya. (1981). The distribution and biology

of killer whales in the Southern Hemisphere. Report of the International Whaling Commission

31:551-566.

16Pitman, R. L., and J. W. Durban. (2010). Killer whale predation on penguins in Antarctica.

Polar Biology 33:1589-1594.

17Pitman, R. L., and J. W. Durban. (2012). Cooperative hunting behavior, prey selectivity and prey

handling by pack ice killer whales (Orcinus orca), type B, in Antarctic Peninsula waters.

Marine Mammal Science. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00453.x.

18Dwyer, S. L., & Visser, I. N. (2011). Cookie cutter shark (Isistius sp.) bites on cetaceans, with

particular reference to killer whales (orca)(Orcinus orca). Aquatic Mammals. 37(2), 111-138.

19Berzin, A.A. and Vladimirov, V.L. 1983. Novyi vid kosatki (Cetacea, Delphinidae) iz vod Antarktiki.

Zool. Zh. 62(2):287-95. [Translated in 1984 as “A new species of killer whale

(Cetacea, Delphinidae) from Antarctic waters” by S. Pearson, National Marine

Mammal Laboratory, Seattle, WA 98115, USA].

20Pitman, R. L., J. W. Durban, M. Greenfelder, C. Guinet, M. Jorgensen, P. A. Olson, J. Plana, P. Tixier

and J. R. Towers. (2011). Observations of a distinctive morphotype of killer whale

(Orcinus orca), type D, from subantarctic waters. Polar Biology 34:303-306.

21Tixier, P., N. Gasco, G. Duhamel and C. Guinet. (2010). Interactions of Patagonian toothfish fisheries

with killer and sperm whales: an assessment of depredation levels and insights on possible

mitigation solutions. CCAMLR Science Series 17:179–195.

22Foote, A. D., J. Newton, S. B. Piertney, E. Willerslev and M. T. P. Gilbert. (2009). Ecological,

morphological and genetic divergence of sympatric North Atlantic killer whale populations.

Molecular Ecology 18:5207-5217.

23Icelandic Orca Project. www.icelandic-orca.com.

24Norwegian Orca Survey. https://www.norwegianorcasurvey.no/.