Over the last four weeks since early January, a total of 29 sperm whales have stranded around the coasts of the southern North Sea from Germany through The Netherlands and France to Eastern England. Many of these stranded alive but died subsequently. Many questions have been asked, and here we attempt to answer them.

The first UK stranded sperm whale at Hunstanton.

Photo by Laurence Clark (Castle Vision Photographic)/ Sea Watch Foundation

The first UK stranded sperm whale at Hunstanton.

Photo by Laurence Clark (Castle Vision Photographic)/ Sea Watch Foundation

How rare an event is this? This is now the largest stranding of sperm whales ever recorded in the North Sea. Mass strandings of this nature are rare although they have occurred over at least the last five hundred years. The last mass stranding in Britain was of six at Cruden Bay (Grampian Region) in January 1996, and before that of eleven on Sanday (Orkney) in December 1994. There have been 14 mass strandings of four or more sperm whales in the North Sea since the 16th century.

Note: that mass strandings of sperm whales in the region are not a new phenomenon. Those strandings also tend to occur in the same coastal localities, and particularly around the southern North Sea. All of the mass strandings recorded have been between November and March.

Has the number of strandings of sperm whales increased? The average was less than one per year until the mid-1980s; since then, the average has remained 5-7 per year.

A diagram to show when and where each of the recent sperm whale strandings in the North Sea took place (click to enlarge).

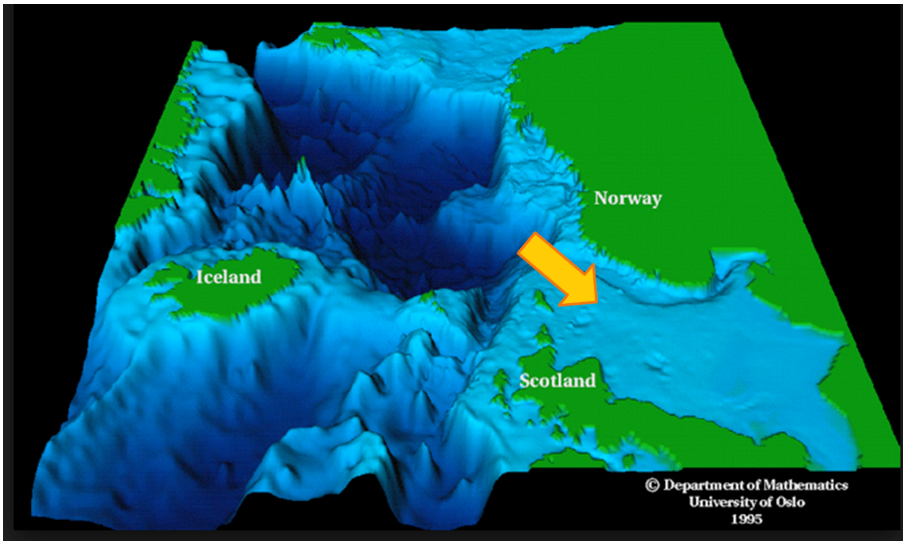

Why have these sperm whales stranded? We cannot be certain of the answer to this but all the evidence points to the following explanation: a group of sub-adult male sperm whales were feeding upon squid in the Norwegian Sea directly north of the North Sea. This is a favoured region for them and for one of their principal prey, squid of the genus Gonatus. The first strandings examined early last month on the Dutch coast contained several remains of Gonatus, as have some of the German stranded animals. More recent strandings have had empty stomachs and the whales have tended to be dehydrated (they obtain water from their prey) suggesting that they had run out of food by this time. After feeding, the whales may have moved southward along the coast of Norway within the Norwegian Trough, a tongue of water of more than 200 m depth stretching down the northeastern North Sea (see eastern sector of Area 1 in the map below, either following more squid shoals or perhaps seeking less turbulent seas in the face of the recent westerly storms. As they ranged further and further south, they entered areas with water depths significantly less than the 500-3,000 metres of the Norwegian Sea and offshore North Atlantic, their usual habitat.

Graphic to show deep sea regions and direction of sperm whale travel from these to relatively shallow North Sea region. Adapted from Department of Mathematics, University of Oslo.

Graphic to show deep sea regions and direction of sperm whale travel from these to relatively shallow North Sea region. Adapted from Department of Mathematics, University of Oslo.

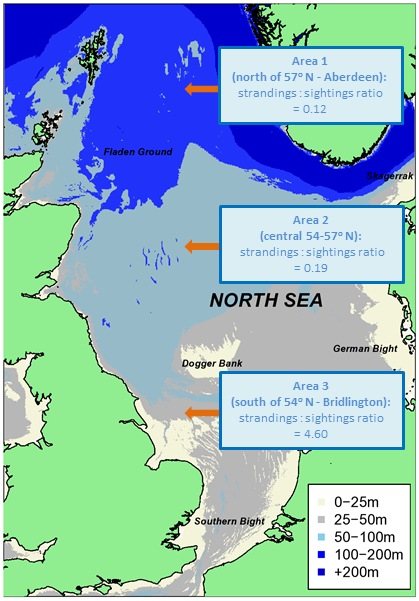

The North Sea can be divided into three regions according to depth: 1) the northern North Sea (north of 57oN) including an area of shelf water 100-200 m deep, and the Norwegian Deep with water depths from 200 to >700 m along the west coast of Norway and in the Skagerrak between Denmark and Norway; 2) the central North Sea (54-57oN) with water depths of 40-100 m (except for the shallower areas on the Dogger Bank and along the west coast of Denmark; and 3) the Southern Bight (51-54oN) with water depth of 40 m or less.

Once sperm whales travel south of the Dogger Bank, they almost invariably strand. If one compares the ratio of the number of sperm whales recorded stranded (since 1990) to the number sighted, there is a significant increase in Area 3 compared with Areas 1 and 2. Not only is this part of the North Sea very shallow, but the areas where they strand are typically gently sloping over mud or sand with depths of 20 metres or less. This makes it very difficult to navigate using the echoes from their sonar clicks. And once the whales are in very shallow waters, the sheer weight of their bodies (young male sperm whales weigh about 20 tonnes) risks respiratory failure following lung collapse as they rest upon the substrate.

Bathymetry map to showing sea depths and ratios of sperm whale sightings to strandings in respective bands of latitude.

Why so many sperm whales? From the early eighteenth century to around 1880, sperm whales were hunted commercially across the world’s oceans. Over that period sperm whale numbers are thought to have declined by almost one-third from around one million animals worldwide. There followed a period of less whaling activity for the species until after World War II, when commercial whaling increased once more. During the 20th century, at least three-quarters of a million were killed, largely between 1946 and 1980, with peak catches in the 1830s and 1960s. In the North Atlantic sperm whales were hunted mainly around Iceland, off the coasts of Spain and around the oceanic archipelagos of Azores and Madeira.

Widespread public concern in the 1970s-80s led to the cessation of whaling in the mid to late 1980s. This seems to have coincided with precisely when strandings in the British Isles, particularly the North Sea, increased sharply.

Sperm whales in northern Europe are invariably males, and usually sub-adults. Female sperm whales largely remain year round in the tropics and subtropics, attended by mature males who for the most part control access to the females. Soon after young males have grown to sexual maturity, they start to leave the breeding groups and migrate into high latitudes. A male sperm whale typically reaches sexual maturity around 18-19 years of age, and measuring a length of c. 12 metres. The animals that strand around the British Isles are usually c. 12-15 metres in length, in other words young adults. The indication therefore is that once whaling ceased (which had often selected for large bulls), there was greater competition for females within breeding groups so that more groups of sub-adults tended to migrate towards high latitudes, hence the increase in numbers of strandings and of groups of young males.

Is there a possibility of a human related cause? When a rare event occurs such as a mass stranding, the natural thing to do is to look for a human related cause. After all, humans more than any other species are the ones responsible for causing extinctions and generally damaging our environment. Thus when people see these magnificent animals in distress on sand banks or mud flats, and there are dozens of wind turbines in the area, the immediate thought is that these might be the cause. However, this is unlikely to be the cause. Wind turbines in operation produce very low frequency sound and if mounted on rock, may transmit vibrations along the seabed. In shallow water with a soft seabed, noise is propagated over rather short ranges, as it gets absorbed into the substrate. Sperm whales are sensitive to much higher frequency sounds. More important, however, is the fact that sperm whales were inhabiting waters far from their normal habitat and well beyond where any wind farm noise or vibrational disturbance could possibly have affected them. And history shows that they typically strand when they occur in the southern North Sea and this has occurred for centuries long before wind turbines had been invented.

Others have suggested that the whales have been affected by noise from seismic surveys in the region. In our view this is also unlikely. Whereas at least short-term behavioural reactions to the low frequency sounds made by seismic have been observed in some baleen whale species, despite several detailed studies there is rather little evidence that sperm whales have responded negatively. They depend very much upon sound frequencies above those seismic sounds carrying the most energy

We cannot discount noise from some source (e.g. mid frequency active sonar) affecting them, but there is no evidence so far to indicate that, and there is a much simpler explanation.

A sperm whale in happier times. Photo by J Gordon/ Sea Watch Foundation.

Can anything be done to prevent such strandings? If it were practicable, one could potentially coax animals out of dangerous shallow areas with a flotilla of boats. However, if the wider region is all pretty shallow, the whales are most likely to strand again. Short of airlifting the whales (which in this situation would almost certainly have been impractical) far away to deep waters north or west of the British Isles, a rescue is unlikely to be successful – sadly.

By Dr Peter Evans, Director of Sea Watch Foundation.

Pingback: liquid cialis

Pingback: Sea Watch Foundation » Whale, dolphin and porpoise strandings…

Pingback: What Causes Whale Mass Strandings? | danielsternklar.com

Pingback: What Causes Whale Mass Strandings?

Pingback: These poor whales! – The Magic Dolphin Blog!