For this species feature, we’re going tropical! Cruising through deep pelagic waters, the energetic, exuberant, and extremely social false killer whale could be regarded as one of the best team-players in the animal kingdom. This blog will take a look at how they got their name, how they look and behave, and the threats they face as their and our worlds collide.

The false killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens, is an oceanic dolphin, and the only member of its genus. The process by which it became classified as we know it today is one with a fair number of bumps along the road. In 1864, palaeobiologist Richard Owen described the false killer whale as a porpoise (Phocoena) in his book ‘A History of British fossil mammals and birds’, based on a 126,000 year-old skull found in 1862. Whilst this might seem bizarre, his decision was based on notable similarities between the false killer whale skull and teeth, and that of a Risso’s dolphin, which at the time was also assigned to the Phocoena group. The nickname of ‘thick-toothed grampus’ (grampus being an alternative name for a Risso’s dolphin, and now its genus name) that Owen gave the false killer whale has somewhat stuck, with ‘crassidens’ meaning ‘thick-toothed’.

“the common name ‘false killer whale’ remains, alluding to the similarities between the skulls of the two species“

That same year, another zoologist, John Edward Gray, decided that it was not a porpoise, and in fact a kind of killer whale, based on the similarities between the skulls of these species – placing it in the genus Orca. Up until this point, classification relied largely on descriptions of the animal and the aforementioned skull; live specimens or in-person observations were scarce. In fact, the false killer whale was thought to be extinct at this point. Finally, in 1862, Danish zoologist and herpetologist Johannes Theodor Reinhart used beached specimens to assign it to its own genus, Pseudorca, recognising that it was neither a porpoise nor a killer whale! Despite this, the common name ‘false killer whale’ remains, alluding to the similarities between the skulls of the two species. In fact, the false killer whale is not particularly closely related to the orca at all! Instead, it shares close relations to species within its subfamily Globicephalinae, which includes the Risso’s dolphin, melon-headed whale, pygmy killer whale, and pilot whales. There are no recognised subspecies of the false killer whale as yet, however genetic, photo-ID and satellite tagging research undertaken in Hawaii (where they are most well-studied) suggests insular and offshore populations are genetically unique, the former classified as endangered (Handbook of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises; Baird et al., 2010; Chivers et al, 2010; Martien et al., 2011).

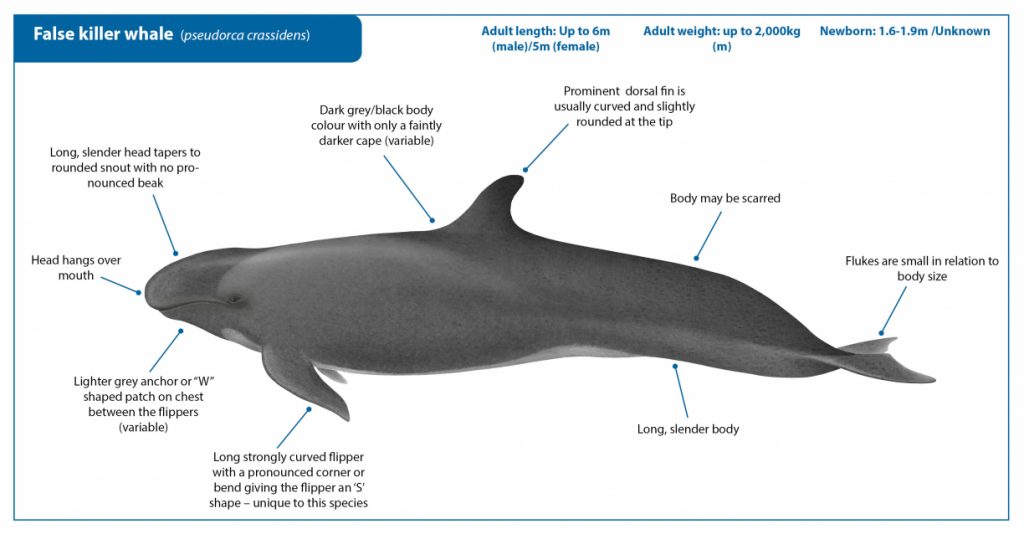

Unlike their namesake, false killer whales look quite unlike the orca we are familiar with. Black or dark grey in colour, they can have lighter patches on their chests and abdomens. Generally, they grow up to 6m in length and though males are often slightly larger than females, the size difference between sexes is not pronounced. They possess a slender body and a small, conical head with no beak, perfect for energetic swimming and leaping clear of the water. Their pectoral fins are uniquely shaped, possessing a distinctive humped shape which creates an ‘S’ shaped profile on their outer edge. Their dorsal fins are usually sickle-shaped and slightly rounded, but this can vary significantly. In some parts of the world, the dorsal fins show long-term impacts of fisheries interactions, such as characteristic injuries (Baird & Gorgone, 2005). Being top predators, false killer whales are naturally rare and encountered infrequently; there is no real population estimate. Typically inhabiting deep, pelagic tropical waters, they have been known to move inshore or around oceanic islands (Baird, 2009).

Whilst dolphins as a group are known to be social animals, false killer whales take this to extreme levels; they are renowned for their interactions with their own species, with other dolphins, and even with humans! They usually travel in groups of 10-60, but groups of 20-100 individuals are not unheard of, and usually these small groups are part of a larger aggregation spread over a large area. Research shows that individuals repeatedly associate in the same groups over long periods of time, and show fidelity to certain sites (Baird et al., 2008). Smaller groups called ‘clusters’ consist of related individuals and are matrifocal in structure, meaning they are led by their older females. Interestingly, false killer whales are included in the small number of animals that experience a long post-reproductive lifespan – essentially, they go through the menopause! (Photopoulou et al., 2017) It’s thought that the evolution of this trait may be based on the proportion of females living past their reproductive stage (Foote, 2008); female false killer whales may regularly live past 60 years old. Having ‘elderly’ females remain in pods despite not reproducing may be beneficial in terms of bringing up young and passing on experience – similar to what we see in the orca and the short-finned pilot whale. Whilst these strong family and social bonds can be beneficial, they can also be detrimental. False killer whales are a species notorious for mass stranding, with the largest event occurring in 1946, where 835 animals stranded in Argentina.

As well as travelling and socialising together, false killer whales also feed in uniquely cooperative ways. After a cluster works together to catch food, dispersed groups will converge on this prey despite it being caught by another sub-group, and they share the catch together. Their diet is thought to be primarily squid and large fish including mahi-mahi, swordfish, and billfish, determined from feeding observations, stomach contents, and fisheries interactions (Handbook of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises; Baird & Gorgone, 2005; Baird et al., 2008; Ortega-Ortiz et al., 2010). A lone false killer whale which inhabited the coast of British Columbia in the 1980s (affectionately named ‘Rufus’) was known to catch large fish and offer them to human boaters and divers, in a similar way to which he would have presumably shared prey with a pod of his own species! Similar interactions have also been reported since, where individuals will bow and wake-ride boats, present prey, and generally appear to seek out human interaction. This surprising behaviour is testament to their astonishing sociality.

Alongside socialising within their own species, false killer whales also interact non-aggressively with other dolphin species, notably bottlenose dolphins, but also Pacific white-sided, spotted, Risso’s, and more. They have frequently been observed forming mixed species pods that associate, feed, and travel together, sometimes over periods of years (Zaeschmar et al., 2012; 2013). This suggests that they can form and maintain friendly, long-lasting bonds with other species. Whilst they can clearly form very positive relationships with their fellow cetaceans, they have also been observed feeding on them; most likely animals that were already weak or injured as a result of injuries sustained from fishing gear. They can also put their teamwork to more sinister uses, including engaging in forms of kleptoparasitism (where one animal takes food that another animal has caught or collected, to the detriment of that animal). For example, false killer whale groups have been observed harassing sperm whales in an attempt to get them to regurgitate squid (Palacios & Mate, 1996). On the other side of the coin, there have been rare accounts of false killer whales falling prey to killer whales (Visser et al., 2010) – so they can’t get too relaxed!

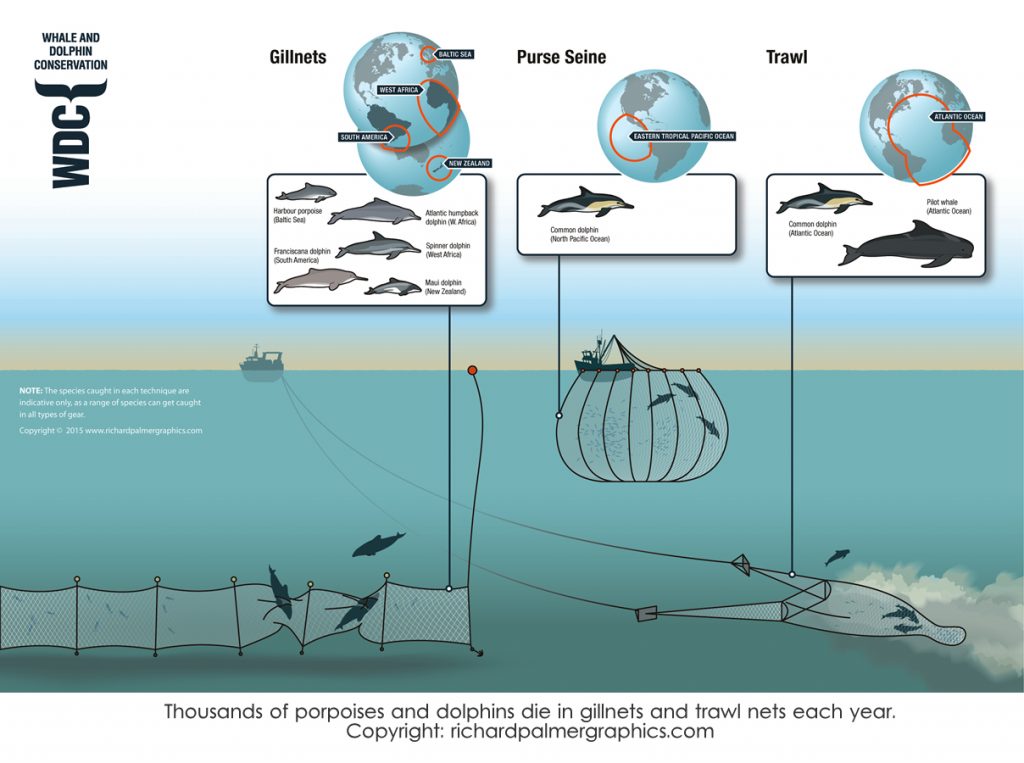

However, the greatest risk by far to this species is fisheries interactions. Animals are often bycaught in fishing gear or injured as they depredate (take food from) long-line, seine, gillnet, and trawl fisheries (Baird et al., 2014; Passadore et al., 2015; Bayless et al., 2017). It is thought that hauling gear may act as a signal or cue to initiate these interactions (Anderson et al., 2020). Individuals can die from sub-lethal injuries, that may reduce their ability to swim, feed, or otherwise function normally, or lethal injuries such as drowning from entanglement. There have also been reports of death by retaliation from fishermen, who may shoot animals to prevent them from taking high-value catch (Baird et al., 2017). Worryingly, there is evidence that females may be more affected than males in terms of lethal fisheries interactions, which could have devastating population-level impacts due to their characteristics of slow reproduction and post-reproductive lifespan. This is especially concerning, considering the number of deaths via fisheries interactions is thought to be above Potential Biological Removal in some populations (this is the number of animals that can be removed or lost from a population, not including those that die naturally, and still allow the population to be at an optimum level) (Baird et al., 2014).

Aside from fisheries interactions, other worrying threats to false killer whales include organic pollutants and heavy metals that accumulate in their body tissues (Ylitalo et al., 2009; Kratofil et al., 2020), which may result in reproductive or immune dysfunction. These pollutants may accumulate more readily in false killer whales than in some other delphinids due to the fact that they prey on such large fish species, as well as other cetaceans. Together, these threats pose significant risks to already vulnerable populations such as that of insular Hawaii. The fact that these animals live in such close-knit communities is also a threat in itself; this may reduce the potential genetic diversity of the population, which then reduces its ability to adapt to environmental changes or disease.

Still poorly understood compared to many cetaceans, false killer whales are a truly fascinating species. But with mounting threats, their future is uncertain. It’s imperative that we find ways to live alongside them, finding solutions that allow us all to thrive, so that in years to come a trip through tropical waters might still be punctuated by a visit from a friendly face from the deep.

Lucy

@lucwhyy

Sea Watch Foundation Volunteer

Feature Blogger

Martien, K.K., R.W. Baird, S.J. Chivers, E.M. Oleson and B.L. Taylor (2011). Population structure and mechanisms of gene flow within island-associated false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the Hawaiian Archipelago. Document PSRG-2011-14 presented to the Pacific Scientific Review Group, Seattle, November 2011.

Baird, R., Gorgone, A., McSweeney, D., Webster, D., Salden, D., Deakos, M., Ligon, A., Schorr, G., Barlow, J. and Mahaffy, S. (2008). False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the main Hawaiian Islands: Long-term site fidelity, inter-island movements, and association patterns. Marine Mammal Science, 24(3), pp.591-612.

Palacios, D. and Mate, B. (1996). ATTACK BY FALSE KILLER WHALES (PSEUDORCA CRASSIDENS) ON SPERM WHALES (PHYSETER MACROCEPHALUS) IN THE GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS. Marine Mammal Science, 12(4), pp.582-587.