Jade Chenery, MSci Marine Biology, Sea Watch Foundation Research Intern 2015.

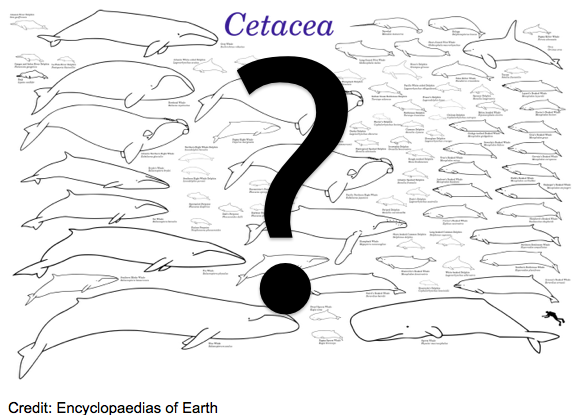

From my dissertation on bottlenose dolphins in Tenerife the interest arose on subspecies and then towards hybrids within cetaceans and everywhere I look there is a different estimate for the total number of whales, dolphins and porpoises worldwide…

How many cetacean species are estimated?

So a species is defined as “A group of closely related organisms that are very similar to each other and are usually capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring”

From a quick google search on cetaceans there is a range of cetacean species number estimates that range from 87-88 (Encyclopaedia of Earth) all the way up to a 125 (ICUN) including the known subspecies and subpopulations.

Hybrids – the offspring of two plants or animals of different species or varieties. Name: Species A x Species B.

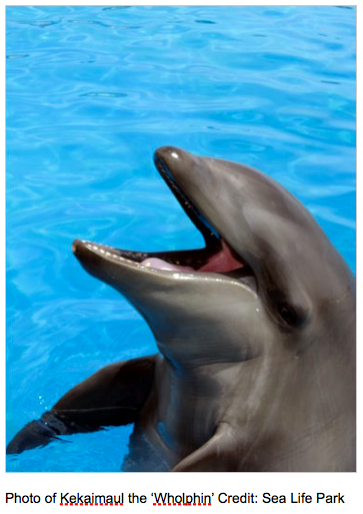

Hybrid marine mammals which are a cross between a dolphin and a false killer whale, despite the latter being dolphins, have been named ‘Wholphins’. Whilst they are believed to exist in the wild the only known examples have been born in captivity. Kekaimaul, meaning ‘peaceful ocean’ was born in 1985 at Sea Life Park in Oahu, Hawaii to a bottlenose dolphin mother and a false killer whale father who shared a pool. Her appearance sits somewhere in the middle of her parents as she is darker than her dolphin mother and has 66 teeth compared to the 88 and 44 teeth her mother and father prosess respectively. Whilst most hybrids are sterile in the wild she has gone on to have 3 calves fathered by a bottlenose dolphin making them ¼ false killer whale. Her first calf unfortunately died after a few days and her second had to be hand reared by trainers and died at the age of 9, however (third time lucky!) she nursed Kawili Kai and they are both still on show to this day in the park.

Hybrid marine mammals which are a cross between a dolphin and a false killer whale, despite the latter being dolphins, have been named ‘Wholphins’. Whilst they are believed to exist in the wild the only known examples have been born in captivity. Kekaimaul, meaning ‘peaceful ocean’ was born in 1985 at Sea Life Park in Oahu, Hawaii to a bottlenose dolphin mother and a false killer whale father who shared a pool. Her appearance sits somewhere in the middle of her parents as she is darker than her dolphin mother and has 66 teeth compared to the 88 and 44 teeth her mother and father prosess respectively. Whilst most hybrids are sterile in the wild she has gone on to have 3 calves fathered by a bottlenose dolphin making them ¼ false killer whale. Her first calf unfortunately died after a few days and her second had to be hand reared by trainers and died at the age of 9, however (third time lucky!) she nursed Kawili Kai and they are both still on show to this day in the park.

The first example of a wild fertile hybrid was proven to be true when a large pregnant female whale was caught in Icelandic waters in 1986 and bore both the physical characteristics of the two largest cetaceans the blue (Balaenoptera musculus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). When the genetics of the animal was analysed it showed that the whale was a hybrid of a male fin whale and a female blue whale and the fetus had a blue whale father. Not only was it the first example of any cetacean hybridisation in the wild but it was also the first evidence of this phenomenon producing fertile offspring.

The first Clymene dolphin was described in 1846 and then confirmed as a species in 1981, Stenella clymene. However it wasn’t until recently that genetic studies recognised this dolphin as a hybrid between the striped (Stenella coeruleoalba) and the spinner (Stenella longirostris) dolphins. It had long been noted that its appearance and behaviour was closer to that of the latter species but its cranial features were similar to that of S. coeruleoalba.

Subspecies: A taxonomic subdivision of a species consisting of an interbreeding, usually geographically isolated population of organisms that exhibits small, but persistent, morphological variations from other subdivisions of the same species.

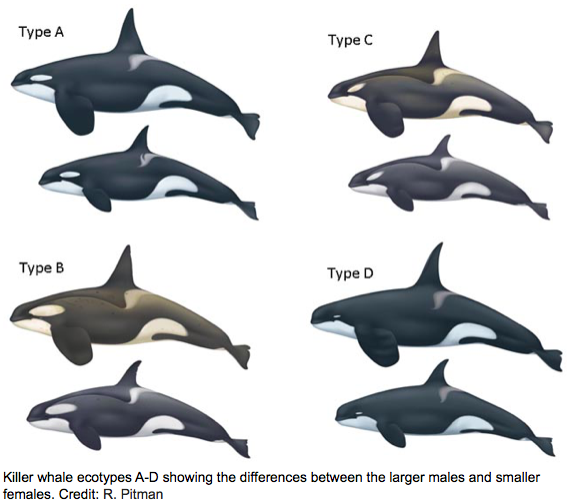

Killer whales (Orca) are found in all of the worlds oceans making them one of the most widely distributed marine mammals, ranging from the polar waters to more tropical waters. Globally, killer whales have all been considered as one species, Orcinus orca. However, recent genetic studies have identified morphological differences between populations indicating the need for multiple species or subspecies of killer whales to be classified. Physical differences are exhibited between the populations of killer whales with their different feeding techniques, prey preference, behaviour patterns, social structures and habitat choices, so interbreeding between these populations is expected not to occur even when their ranges overlap.

Whilst the killer whales are roughly split into 4 types: A, B, C and D worldwide, many of these within an area have been split even further. In the eastern North Pacific Ocean three forms (ecotypes) are recognized: Resident, Transient and Offshore in which the ecology, appearance, diets, behaviour and genetics all differ, however the populations within these ecotypes share some of their home ranges.

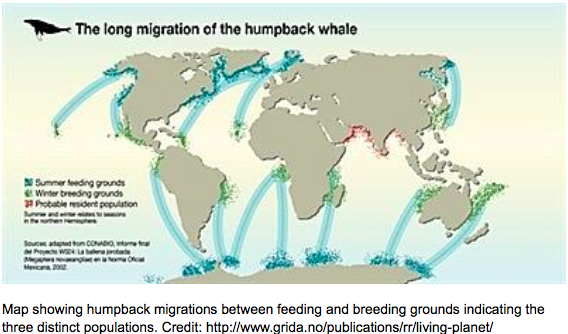

Last year a genetic study started to unravel that potentially the three North Pacific, North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere populations of humpback whales may actually be subspecies. Researchers discovered that the subpopulations may be more isolated from each other as they rarely cross paths during their migrations. The darker colouring on the underbellies and tails of the northern whales may be explained by this isolation and suggests that the different populations are evolving independently. Further backed up with genetic studies this seems to have been occurring for many years. If this goes on to classify three distinct subspecies it could mean that the populations are more at risk than currently thought as emigration between oceans would not ‘top up’ population numbers.

Now bringing it closer to home we’ll look at the bottlenose dolphin which is regularly seen around the UK. Depending on where you read, the ‘bottlenose dolphin’ refers to one species (Tursiops truncatus) whereas other sources describe three species that fall under the term: the common bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus), Indo-pacific bottlenose dolphin (T. adunctus) and the Burrunan dolphin (T.australis). The latter was recently described in 2011 as research showed distinctions from the other two. Two subspecies are then further recognised within T. truncatus, the first being the Black Sea bottlenose dolphin (T. t. ponticus) and the Pacific bottlenose dolphin (T. t. gillii). Further to this there are two ecotypes that exist within the bottlenose dolphin, the coastal and offshore individuals. Coastal bottlenose dolphins tend to be lighter in colour and smaller in colour and whilst their ranges overlap they have been shown to be distinctive genetically in the North Atlantic, although they have not been as yet separated into sub species or species.

Now bringing it closer to home we’ll look at the bottlenose dolphin which is regularly seen around the UK. Depending on where you read, the ‘bottlenose dolphin’ refers to one species (Tursiops truncatus) whereas other sources describe three species that fall under the term: the common bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus), Indo-pacific bottlenose dolphin (T. adunctus) and the Burrunan dolphin (T.australis). The latter was recently described in 2011 as research showed distinctions from the other two. Two subspecies are then further recognised within T. truncatus, the first being the Black Sea bottlenose dolphin (T. t. ponticus) and the Pacific bottlenose dolphin (T. t. gillii). Further to this there are two ecotypes that exist within the bottlenose dolphin, the coastal and offshore individuals. Coastal bottlenose dolphins tend to be lighter in colour and smaller in colour and whilst their ranges overlap they have been shown to be distinctive genetically in the North Atlantic, although they have not been as yet separated into sub species or species.

Extinctions?

In recent years the ‘first-human caused cetacean extinction’ hit the news as the Yangtze River dolphin aka Baiji (Lipotes vexillifer) was functionally declared as being extinct. The freshwater dolphin had been long recognised as one of the rarest and threated marine mammals and was endemic to the middle-lower region of the Yangtze River and Qiantang River in China. The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) still lists the species as ‘Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct)’ but the last photographic evidence of the animal dates back to 2002. A study in 2006 carried out a search of the dolphins’ historical range using multiple vessels and acoustics over 6 weeks but failed to find any evidence of the species existence. Its demise has been linked to unsustainable by-catch and degrading human impacts on the ecosystem of the Yangtze.

A rise in hybrids and eventually subspecies could indicate that populations may be in trouble. If individuals are choosing to breed with another species it could be a sign that encounters with the same species may have, and still could be, dwindling, especially for the larger more solitary whales that travel miles to breed. This however doesn’t explain why dolphin species in pods are deciding to breed with other species. Some of the evidence here for hybrids may have occurred many years ago and it hasn’t been until recent scientific improvements that these have been discovered. Again, with subspecies, science appears to be unlocking numerous subspecies within a species which may have begun to diverge evolutionarily thousands of years ago. There could also be many other examples of hybrids and sub species out there that are yet to be discovered.

Whilst many of the larger once hunted species are still recovering from whaling, species such as the North Atlantic and Pacific right whales are not out the woods yet and some of the smaller cetaceans (e.g. Vaquita porpoise) are at risk from more indirect human impacts such as fishing entanglement and by-catch, habitat degradation, noise pollution and contamination. Throughout evolutionary history there have been 100’s of cetacean extinctions, but today we need to ensure that our modern day cetaceans do not face the same fate at the hands of humans.

The bottom line is that all of this is very complicated! Cetaceans are very difficult to study, especially genetically, due to the short time they spend at the surface. However compared to the 900,000 estimated number of insects and 10,000 bird species you would think we could estimate the number of cetaceans quite easily! Along the way I haven’t really come to a conclusion on the exact number of species within the cetaceans, it’s just again highlighted that science once more is a very complicated world with multiple definitions and classifications. What’s important is that these beautiful animals are continually studied and conserved to ensure that the estimated number of cetaceans species only goes one way and that’s up!

Links: