Monitoring cetaceans can be a tricky business. Fighting against changing sea states and galling winds can make it difficult to spot cetaceans. But with the magic of passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) we can hear them. With PAM we have a window into the behaviour of cetaceans that can provide data vital for their conservation.

Marine mammal species can be extremely social animals, with many using sounds to communicate and socialize among themselves. Some whales, such as the humpback whale sing songs, especially during the breeding season, where the males in whole populations will sing the same song, with slight changes occuring as the season progresses. Orcas are even known to have developed their own family dialects.

PAM uses hydrophones to pick up the different sounds made by cetaceans, from the deep moan of a blue whale to the high-pitched clicks of harbour porpoise. PAM has allowed us to monitor cetaceans even when there is nothing to be seen but waves.

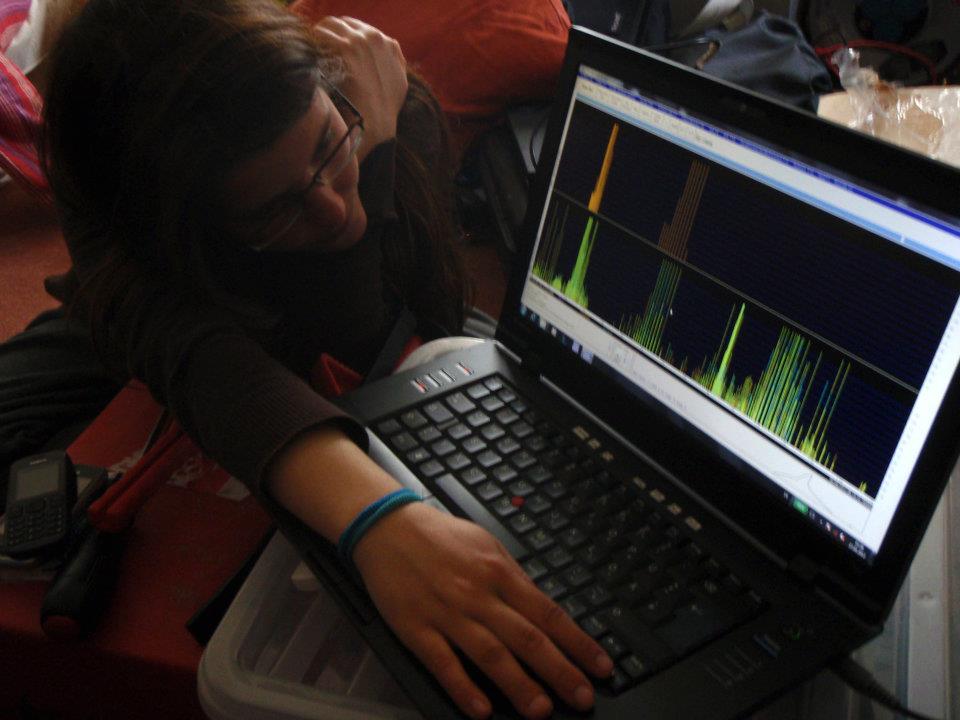

The harbour porpoise for example is ultrasonic, which means we can’t hear them. PAM is able to bypass this issue by producing spectrograms which show the sounds being picked up by the hydrophone, in the form of moving waves.

Due to the high frequency of porpoise vocalisations not only can we not hear them, but their sound doesn’t travel very far, using PAM a harbour porpoise can only be heard from <300m away.

The greatest challenge with PAM is finding the sounds of interest to you within the recordings. We can use the signals to measure abundance and patterns of activity, especially where visual observation can be difficult.

A blue whale can be heard up to 500 miles away (if you can hear sound with a frequency that low!). It would be near impossible to spot a blue whale from that distance.

PAM not only allows us to ‘find’ cetaceans more, it also allows us to protect them.

Seismic survey ships usually carry PAM workers to help protect marine mammals from the loud sounds their air guns produce. This is because although ships have marine mammal observers (MMO), it can be difficult to get and keep a visual on cetaceans, especially as some individuals have been tracked to dive for an hour. With the longest known dive being a Cuvier’s beaked whale which dived for 2 hours and 17 minutes. Although cetaceans may not constantly make noise, many species use clicks to echolocate and sound travels further than we can see, using PAM allows us to mitigate work which could injure cetaceans. For example, a seismic survey air gun array usually fires every 10-15 seconds and can be heard thousands of miles away. The noise produced is second only to shipping noise in contributing to overall ocean noise pollution. This is why PAM is so important, as it can allow us to mitigate seismic survey work until it is safer for marine mammals.

Sound provides us a visual to cetaceans in the area which our eyes can’t. Using the frequency of the sound species can be narrowed down, with the smaller species often having a higher pitch and frequency, whereas the larger species have a lower pitch and frequency. MMO is also important though as it can allow us to get specific identification of species, as well as monitor visual behaviour and the presence of calves.

Written by National Whale and Dolphin Watch Assistant, Lauren Fidler