As Sea Watch interns we are provided the opportunity not only to study marine mammals in the New Quay area, but, thanks to helping manage the national sightings database, also to cetacean-watch vicariously through the eyes of Sea Watch volunteers throughout the UK! It is now May, and that means our volunteers in northern Scotland are gearing up for an annual migration of orcas through the Pentland Firth, ready to host the fifth annual week-long Orca Watch (of which we are only a little envious… I swear).

Duncansby Head, one of the locations observers in last year’s Orca Watch saw orcas. (© Anna Jemmett / Sea Watch Foundation)

Orcas have piqued my interest for much of my life, and I suspect a number reading this blog may feel similarly. If you fall into this category and are reading this blog, I hope you will forgive any banality within information presented here. If not, I hope it piques your interest as well!

Why the interest?

The orca (Orcinus orca), despite its other common name of killer whale, falls within the dolphin family. Both names hark back to a historical recognition of its position as an apex predator, with orca referring to Orcus, a Roman god of the underworld. Despite the names wild populations present no danger to humans, and nowadays they are studied to understand their diverse ecological adaptations, intelligence, and family-based social structures. It’s a tad too much to cover in one reading, so this post focuses on an area that particularly interests me.

Additionally, orcas simply look really cool. (© John Irvine / Sea Watch Foundation)

A truly cosmopolitan species, with populations spread throughout every ocean in the world, orcas have adopted a variety of lifestyles, often based around prey choice. Different cultures emerge, which pass down through generations due to elder pod members (orcas may potentially live longer than a century) teaching younger ones. Studies in the past couple of decades have found that populations of different cultures not only eat different prey to each other, but seem to live completely independently, not socialising or breeding with each other despite sometimes living in the same waters. These separate populations are referred to as “ecotypes”.

This process of separation due to behaviour, possibly leading to the eventual development of two populations into separate species (known in the lingo as “sympatric speciation”), is of great interest to scientists, being a theory that is much harder to observe and prove than the more easily understood speciation due to geographic separation (in the lingo “allopatric speciation”). Orcas have provided possibly the best example of sympatric divergence currently known, with divergence to the extent that some scientists have suggested splitting orcas into multiple species.

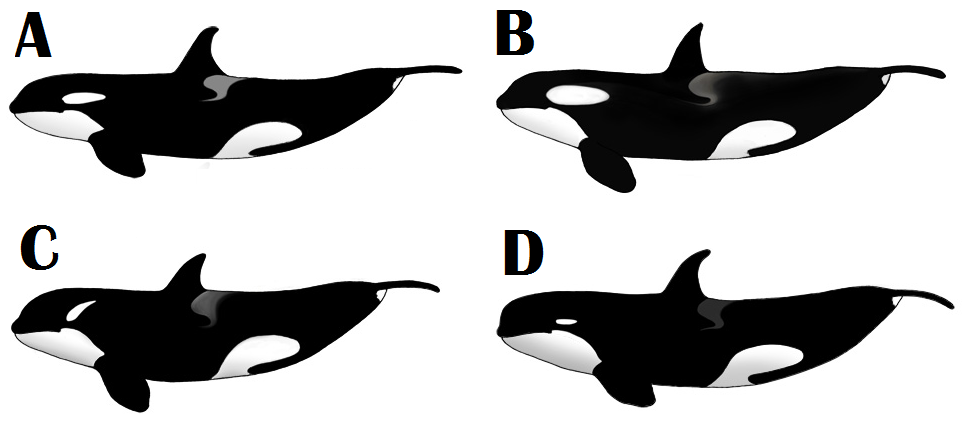

The development of distinct ecotypes was first discovered and studied in orcas in the north-east Pacific, where three separate ecotypes have been identified, “residents”, “transients”, and “offshore”. Orcas in these ecotypes differ not only in prey choice, but also in morphology, behaviour, and social structure. The next-best studied populations are those of Antarctica, where three, possibly four, ecotypes have been named by less imaginative scientists as ecotypes “A”, “B”, “C”, and the rarer and relatively unstudied “D”.

The four Antarctic ecotypes have clear morphological variations. (CC BY-SA 3.0 Albino.orca / Wikimedia Commons)

The North Atlantic populations are less well-studied, but currently there are two identified ecotypes, named with similar creative nous to the Antarctic ecotypes as “type 1” and “type 2”. Type 1 is made up by populations ranging from Newfoundland to Norway, and are thought to be generalist feeders that reach a maximum length of around 6.6m. Type 2 are thought to be specialist feeders of other marine mammals, and are larger than type 1, reaching lengths of up to 8.5m. So far type 2 have been seen to the south and west of the type 1 ranges, although it is suspected that at least historically they overlapped to a great degree. Watchers in the UK are fortunate enough to be in the position to potentially see both types, type 1 off the northeast of Scotland and type 2 down the western coast.

The role of watchers

Our dedicated whale watchers (led by Colin Bird and perhaps including you!) will observe orca numbers and behaviours as they pass through the Pentland Firth during the week of 21-28 May. They will also be taking photos, which will be added to a photo-identification database in order to identify individual orcas. Dolphins can often be identified by their dorsal fin, which is easy to see while out of the water, and will have a unique combination of shape and scars. Orcas are especially good for photo-identification, as they have massive dorsal fins that can reach as high as 1.8m. Furthermore, they have various white patterns on their body, including “saddles” (do not attempt to use as an actual saddle) behind their dorsal fin and eye patches, whose shape will differ between individuals.

Dorsal fins, eye patches, and saddle patches provide unique marks to identify individuals. This photo was taken during a previous Orca Watch! (© Colin Bird / Sea Watch Foundation)

The orcas we expect to see during Orca Watch are type 1 orcas migrating to summer feeding grounds. Previous years have identified individuals from this migration as the same as some that were seen feeding off Iceland! It is currently thought that they come to the Pentland Firth and nearby areas in order to hunt seal pups when herring stocks are low elsewhere.

Sightings work done during Orca Watch will help us to understand more about these animals. The resulting information will give us insight into their abundance, distribution, migration routes, prey choices, social life, and potentially much more. Such information will also help inform future research and conservation efforts, so that future generations can have the same experience of seeing orcas that current Orca Watch volunteers will have.

For those not convinced of participation yet, sightings are not limited to just orcas! Minke whales are often seen, along with the smaller common dolphins, and the tiny harbour porpoises. Last year Orca Watch participants even saw a humpback whale! Nesting in the surrounding cliffs are guillemots, a joy to watch clumsily fly around. Kittiwakes, skuas, and puffins also make their homes in the area.

Although both are black and white, guillemots and orcas can be easily distinguished by their size. Photo from a previous Orca Watch. (© Colin Bird / Sea Watch Foundation)

If you are unable to participate this year, don’t worry too much, hopefully you’ll be able to come in a subsequent year! For those who want to participate, for anything from a couple of hours to many days, we look forward to having you join us! (By which I mean those of us on the watch. Personally, I will, I’m afraid, be behind my keyboard here, waiting for the photos to roll in.)

A full itinerary of the week’s events can be found at http://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/orca-watch-2016/

A recap of last year’s Orca Watch can be found at http://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/sensational-sightings-at-orca-watch-2015/

Author: Thomas Bell (Sea Watch intern 2016)