Kristina came to Sea Watch in 2015 as a Research Intern and we’ve kept in touch since. In January this year, she wrote a blog about her seal research and has drawn comparisons with our work on dolphins too

I was an intern for Sea Watch Foundation in 2015 (an experience that I can only recommend to everyone!). Apart from amazing dolphin experiences, this internship also brought out my interest in seals. The Research Assistant at the time started a photo-identification project for seals within Cardigan Bay and being fortunate enough to volunteer during the grey seal pupping season, I had very many happy seal moments. I am now doing a research masters at the Marine and Freshwater Research Centre at GMIT in Galway, Ireland. When Kathy asked me to write about my project, I couldn’t have been happier!

Grey and harbour seals are the only two pinniped species found in Irish waters, where their population structure and genetic diversity is currently unknown. There have also been two past virus outbreaks (the Phocine Distemper Virus for anyone interested). These outbreaks resulted in massive die-offs of European harbour seals and may have decreased their diversity (grey seals were not affected by the virus). This is why I aim to assess population structure and long-term changes in genetic variability. It’s a very exciting project as I hope to provide information on connectivity and reproductive isolation among geographical areas which will help to identify management units for this species. These management units are necessary for the production of effective management plans to aid the conservation of these species in Irish waters where they are protected under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. However, I am also collaborating with partners outside of Ireland, acquiring samples from the UK and Europe to get an idea of the broader picture.

For the sake of the animals, I will be using non-invasive sampling techniques. This means that there will be no necessity of capturing individuals in the field. I will use scat samples (yes, this is just a fancy word for poop) and hair samples. You might wonder why hair is required especially in case it needs to be plucked from the animal. Let me tell you: I am not targeting this specifically but young pups do have a fairly liquid poop which makes it hard to sample in the field. That is why I take hair samples from these animals. But of course we do not want mum to abandon her pup, so that’s why only independent pups are sampled for hair! Obviously, as conservationists, we do not want to increase pup mortality with our presence!

During the current grey seal pupping season, which is reaching its end, I have been able to go out and get quite a few samples (mostly hair, but also scat samples). I would love to show you all how this would look, but unfortunately you need a licence to take photographs of the animals at breeding sites. Here is a picture of where we have been going out. It was like seal haven, soooo many! I hope you will enjoy it without the seals

Figure 1: The south island of the Inishkea group. This island as well as the north island supports a large grey seal breeding population.

Figure 1: The south island of the Inishkea group. This island as well as the north island supports a large grey seal breeding population.

Besides going out in the field myself, I have also established collaborations with various institutions/organisations including seal sanctuaries, aquaria, and museums, in order to increase sample size. This is really important for the project, especially when broadening the picture to outside of Ireland as I obviously cannot go and sample everywhere myself! At the moment, one of the most important collaborators is Seal Rescue Ireland. I am in constant contact with them and they have had loads of pups in over the course of the season providing me with scat, hair and mouth swab samples of all their seals. I can’t thank them enough, it’s been really good for me in terms of samples

Figure 3: This is the nursery pool at Seal Rescue Ireland; the first pool where seals go to once they are gaining weight and feed themselves. The paint does not harm the animals and helps the team to recognise individual seals more quickly.

Figure 3: This is the nursery pool at Seal Rescue Ireland; the first pool where seals go to once they are gaining weight and feed themselves. The paint does not harm the animals and helps the team to recognise individual seals more quickly.

So now that I already have loads of samples, what’s next? Well, it’s lab time for me! I am extracting DNA from all the samples and again testing the best methods to do this. I have already isolated DNA from hair, so now I am looking at scat and skeletal samples. Once that is done, I can also send DNA off for sequencing and analyse population structure. This brings us back to our goal of informing management policies by identifying separate units within the population.

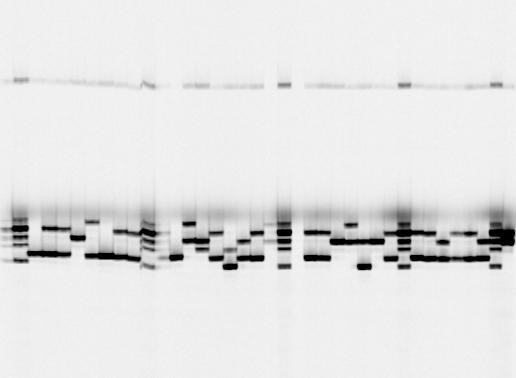

For harbour seals, I am also planning on looking at habitat use within two designated Natura 2000 SACs (areas where the species is legally protected) starting early 2017. To do this, I will look at the DNA in my samples with a certain type of genetic marker: microsatellites. These are very short regions in the nuclear DNA and by looking at several of these markers for each of my samples, I will be able to identify individual seals within the area! Pretty cool, right? That way I can see how specific individuals use the area throughout the year! Below you can see a picture of how a gel image would look like (Fig4). Every so often we would add a ladder which is the well that has many bands showing in the gel. These are of known size so that we can see what size the two alleles of an unknown sample have. There should always be two alleles visible though sometimes they would be of the same size and you would see a single band only (see e.g. well no. 5 of Fig.4).

Figure 4: Gel image using a microsatellite marker. Image taken by Dylan Berrett.

Figure 4: Gel image using a microsatellite marker. Image taken by Dylan Berrett.

This might be a little boring if you are not into genetics though. So Instead of going into too much detail, I’ll insert a little something about photo-identification of seals here! It’s not necessarily going to be part of my project, but it is very useful to identify individuals and could also be used for habitat use. I have worked on photo-identification mostly for dolphins and turtles. But then I got involved with the Sea Watch Foundation where I learned a lot about it regarding Atlantic grey seals! Essentially, the pelage pattern is unique for each individual seal, like your fingerprint. Same as with the dolphins, you could run through all photographs and match individuals manually. However, the Sea Watch Foundation is investigating the efficiency of software to identify individuals using an automated process. The software used is called ExtractCompare (It’s free too! So if you always wanted to try, feel free to give it a go ;)) and it can use different areas to identify a seal, i.e. the flank (side view), the abdomen (belly view), the chest or the neck. Here’s examples of how those areas might look after being entered to the software (taken from the tutorial available from their website):

Figure 5: Examples of different areas that can be used for pattern extraction.

Figure 5: Examples of different areas that can be used for pattern extraction.

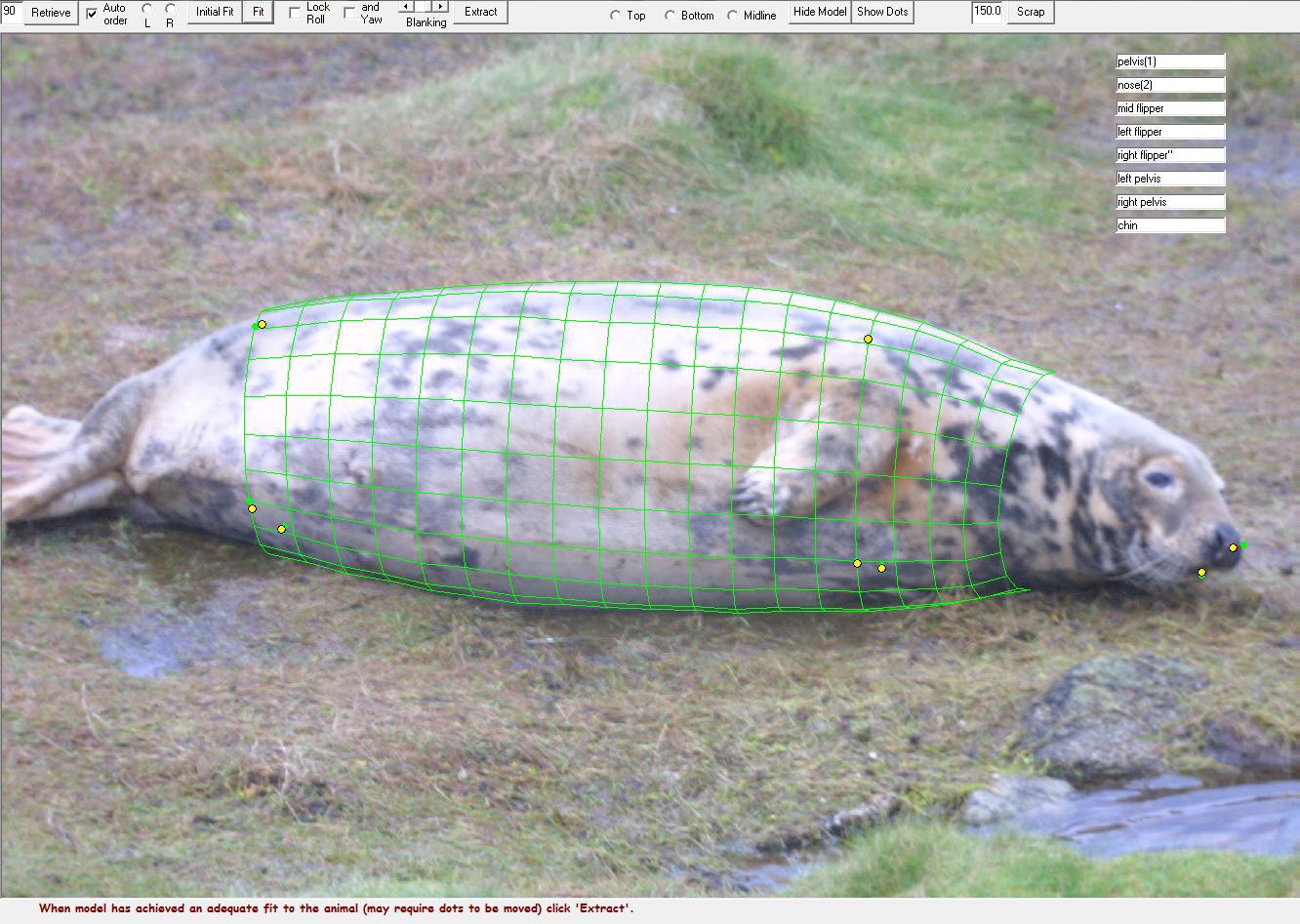

The software will create a 3D model to fit the shape of the seal. The initial fit might not be ideal, but you can edit and fit the model again so it best lies around the individual. This might look something like this (again, this it taken from the software’s website):

Figure 6: 3D model that fits the outline of the seal

Figure 6: 3D model that fits the outline of the seal

From this, the software will extract a 2D pattern that will be used to compare it to previously extracted patterns within the database. I won’t go into details here as that would be too much. Whoever is interested, feel free to check out their website though! Sea Watch Foundation is aiming to create a catalogue of grey seals and to compare it with other catalogues from within the Cardigan Bay area. With this kind of information, it might be possible to estimate abundance or else it would still provide information on movements and habitat use.

By Kristina Steinmetz, Research Intern 2015