Sea Watch Foundations’ prestigious status as the longest-running Nationwide research charity in the UK focussed on the conservation and monitoring of cetaceans, has at its core the selfless donation of time and effort made by a network of dedicated volunteers spread across the British Isles.

The vital science we provide to policy-makers on the health (or lack therof) of the marine ecosystems surrounding the UK and of the marine mammals that call them home, is only made possible by unpaid members of the public reporting what they have seen and talking to us about their encounters.

So called ‘citizen science’ like this is a rapidly emerging and increasingly widespread research tool, especially true since the global financial crisis of 2008 and the economic downturn that followed meant that belts must be tightened, leaving many now shackled to the mantra “do more with less”

The increasing employment of citizen science however provides the dual opportunity to not only cost effectively gather large data-sets across large spatial and temporal scales that are credible and are at fine resolution, but also serves to engage the wider public. This has the very welcome effect of fostering collaboration and helping to bridge the often cavernous gap between the general public and professional scientists. An essential tool for a crisis discipline such as conservation that needs as much support as it can get.

It pleases me greatly in fact to say that this author is certainly not immune to seeing the benefits of its use. While now taking my first bold steps into the scientific world at large as a recent MSc. in Wildlife Conservation graduate, I too used an on-going citizen science based study as the guiding framework that would support my Masters thesis.

Whale and dolphin species will always elicit an emotional response in us. Whether that be fascination or fear, respect or pity, we will always feel something for these large, powerful and charismatic creatures who live in a world that is so entirely alien to us. Indeed Herman Melville in his seminal work Moby Dick hints at this enchantment by telling us “the whale fishery surpasses every other sort of maritime life in the wonderfulness and fearfulness of the rumors which sometimes circulate there”.

It is for this reason that research on whales and dolphins and citizen science marry so perfectly.

Never could this point be more perfectly made than by the context underpinning a very kind email recently sent to Sea Watch by Mr. Kevin Hall, an MSc(Res) student interested in demographic crises in 17thc Scotland and currently working on his thesis regarding historical governmental responses to famine.

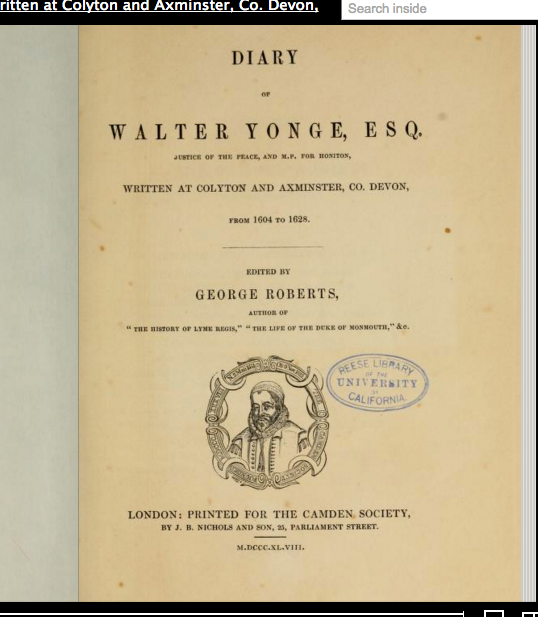

Mr. Hall had been reading a relatively obscure (depending on what your sphere of interest is) diary published in 1622 diary for a Walter Yonge, a 17th century politician, Barrister-at Law, Justice of the Peace, Sherriff for Devon and Member of Parliament for Honiton, when he happened upon a passage describing the stranding of what is thought to have been a pilot whale.

Hall writes, “I had just started leafing through the diary’s entries for 1622-23, when I saw that story about the ‘great fish’ and immediately thought that so

meone must surely have an interest in historical sightings of whales around the coast of Britain. A quick Google search led me to your website and from there, I followed the links to you”.

The context to be considered here is that Yonge’s diary came over 200 years before Moby Dick was written in 1851, and even farther before the British museum of natural history, in an attempt to expose some of the mysteries surrounding these huge and strange creatures found on beaches, started recording cetacean strandings in 1913. Certainly then this must surely be one of the very earliest accounts of a whale becoming stranded on a British beach?

Taking a step back then and taking a wider view: neither Messrs. Yonge nor Hall were in any way directly professionally involved with any form of whale and dolphin research, but have now been united across time by their common enthusiasm to share their findings about these wonderful creatures with others. Yonge shared his interest by viewing the initial experience as interesting and noteworthy enough to be published, and Hall did so by reaching out a collaborative hand to share his finding of the account almost 400 years later.

Melville wrote that “It is not down in any map; true places never are” when describing the Polynesian island from which Ishmael, the story’s intrepid narrator, embarks on his epic voyage with Captain Ahab aboard the Pequod.

This author has the distinct suspicion that, if asked why they continue to selflessly contribute their considerable time and effort to helping us contribute to cetacean conservation, the vast majority of our highly valued citizen scientists might find it difficult to locate an exact reason why. I suspect this is because, for them their wonder for the animals they see and their enthusiasm to share is their truth and can therefore not be found on a map or be described.

Whatever the reason, our vital science is fueled by your endeavor and we are hugely grateful.

Author: Derry Gibson (Sea Watch Research Intern 2016)