Progress doesn’t have to damage wildlife: new developments around Wales can create win-win situations for wildlife and people.

Following a path in Rhosson, which sticks to the beautiful Pembrokeshire coast like an old and trusty friend, I look to the west. From here it is possible to see the shimmering waters and the outline of Ramsey Island on the horizon. The peace and quiet makes this tranquil scene look like the perfect refuge for wildlife. Not far from the mainland, it looks untouched by human hands. Yet underneath the water, it is much easier to see the influences of man.

The proposed tidal turbine project aims to produce green power from the shifting tides around this part of the coast. Whilst these tidal turbines under the water may be beneficial for the industry and the country, they pose a risk to the grey seal populations that live and breed on this part of the Welsh coast.

Mumble in Swansea.

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

A team of researchers are looking into this problem, trying to discover if the turbines are having an effect on the seals.

Mumble in Swansea.

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

A team of researchers are looking into this problem, trying to discover if the turbines are having an effect on the seals.

“In Pembrokeshire we have a company called Tidal Energy Limited. They are a Tidal Energy Industry that have built Wales’ first tidal turbine. They built it under the sea and it sits in between Pembrokeshire and Ramsey Island. But on Ramsey Island there is a large population of grey seals and one of the perceived risks is collision with the turbines,” says William Kay, a PhD student in Swansea University. “Grey seals are very inquisitive animals, so they may go near the object purposely to study it”.

According to the report ‘Blue New Deal 2015’, produced by the New Foundation Economics (NEF), the company is aiming to provide energy for a number of homes close to 10,000 and sustainable employment opportunities for local business by 2017.

In order to understand the impact this project may have on grey seals, researchers first need to track their movements around turbines; “We want to see if the turbines will affect their movement and behaviour in the longer term…… Grey seals move quite a lot but some breeding locations are on Ramsey and Skomer Island – where they come back each year”, says Luca Borger, professor of Biosciences at Swansea University.

Professor Luca Borger, Swansea University

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

Professor Luca Borger, Swansea University

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

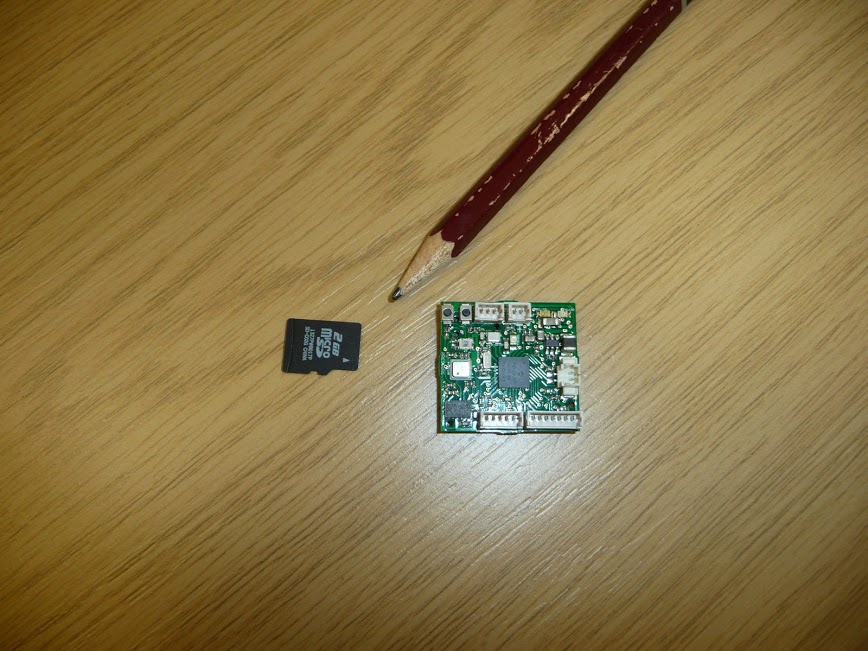

A small tagging device developed, by the team at Swansea University, tracks pressure, temperature, location and depth, providing more information on movements than any other tracking device. This is important, as in addition to the risk of direct impact, tidal turbines may also change the turbulence of the environment, which will affect how the seals travel and forage. By using the new trackers, researchers will be able to understand energy expenditure, how seals interact with the installation, how this is affecting their behaviour, and what they do during the day.

“We want to see two things: firstly, if it is affecting their movement, behaviour and, in the longer term, if it is having a demographical effect. Because these are the two key regulatory things. What we want to know is if this is fine or whether we have to change something,” says Luca Borger.

The project will start with juveniles seals. This way, they’ll be able to apply the device quickly with just a little bit of glue and without having to sedate them. “The data is stored on a small SD Card. We will have some system that, after a month or so, it just drops off and it floats on the surface. We are trying to decide what method we will use to get them back,” he says. The population of grey seals in West Wales, including Pembrokeshire, is estimated to be around 5,000 animals – with 1,400 pups born every year. Mapping the juveniles movements will allow the team to assess their proximity to the turbines when they are at a naïve life-stage and may not yet realise the risk.

The daily diary and SD card used for tracking grey seals

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

The daily diary and SD card used for tracking grey seals

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

The grey seal pupping season starts around October in Ramsey, and, after a month the pups start leaving the beach to become more independent. “That’s when they first enter the water. The months from October to January are quite critical, in the life stage of a juvenile. So you would advise the industry to reduce the amount of operation or turn it off. You can say maybe during the flood tide they can operate the turbines but it maybe that during an ebb – which is typically weaker than a flood- seals may operate in that area. You might be able to advise the industry to operate only at a certain stage…..Then you get the balance of being able to operate as much as possible with minimum risk to marine mammals” says William Kay. This scenario would represent a win-win situation for the industry and wildlife. More than half of the energy in UK comes from the seas and there is a big potential for renewable marine energy. In fact it can reach more than six times the annual demand of electricity, according to the Blue New Deal. Wind turbines, for example, can become equally beneficial spots for the recreation of oyster reefs, where fishing is not allowed and, at the same time, produces green energy.

Expert environmental advisors like Chris Baines are working hard to make sure efforts in development and conservation and achieve the common goal. “I think it is relatively easy for development to be a part of the solution rather than part of the problem for conservation and environment,” he says. Part of the development process can, in fact, create and conserve habitats for wildlife. Equally important is the relationship between developers and conservationists; “The conservationists need to build relations with developers before there is a conflict, by working alongside the non-contentious projects. Then what you have is a relationship, which means that you have better conversation when there is a point of conflict or a problem. And then both sides need to be creative,” Chris Baines says.

Letting people know about the good examples and encouraging them to follow is an important part of the process. The renewable energy sector is growing fast in UK and over 51,000 jobs are offered by this part of the industry alone; however, 86% of the energy still comes from fossil fuels.

The Pembrokeshire Coastal Forum (PCF) aims to promote a sustainable development of the Welsh coast and aims to be part of the mediation between conservationists and developers. “I think the tidal turbines in Ramsey is a great example about how it takes a long time to see results from these projects, because it is in a very sensitive area. It sits within a SAC (Special Area of Conservation), and the island itself is a site of Specific Scientific Interest. There is lots of marine life there, including seabirds, seals, and porpoises. It’s taking a long time to say how they develop the device,” says Paul Renfro, Sustainable Recreation Coordinator for the PCF. “I think it is an exciting project with renewable energy in Wales, you want to keep those wild places special”.

A view of Cardigan Bay from New Quay, Ceredigion.

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

A view of Cardigan Bay from New Quay, Ceredigion.

Photo credit: Marta Montanari

The hope is that, as communication and understanding as improves, a better process can be established. “Pretty much all our projects have those community stakeholders at the heart of it. I think there are about 60 different members of the working group now and that’s a lot of different developers, a lot of conservation bodies talking, and other people talking and working together. I think that is the real key thing, that you are doing things in partnership” says Paul.

Projects already developed include EEP – Ecobank (Ecosystem Enterprise Partnership) and the GIS (Geographic Information System) Mapping software. In the first case there is the involvement of land managers, industry conservation managers and communities, including all the stakeholders. They’re all fighting for the project, which they believe will not only potentially grow the local economy – but save the environment at the same time.

The main concern in the area is the loss of biodiversity and the possibility of encountering difficulties during development. However, projects like the EEP have a different approach to managing natural resources. In the same way the GIS mapping started to survey what was happening in Wales (such as touristic activities and recreation) and record it. That would allow people to know more about it but also let developers understand where there was already too much pressure on nature.

Written by Marta Montanari