This is the latest post in a series which will look at recent advancements, discoveries and trends in the study of whales and dolphins. We here at Sea Watch believe strongly in the free sharing and dissemination of scientific literature and want to give you, our loyal members, the breakdown of all that’s going on in the field.

Narwhals are among the most unique looking animals on the planet. Shrouded in mystery, these unicorns of the arctic are among the least understood and distinctive cetaceans in the world. Male narwhals possess a single spear like tusk, which protrudes from their upper lip, and can grow up to 3m long (Graham et al., 2020). Unlike most tusked animals, the narwhal’s tusk grows straight, spiralling as it does so- an adaptation believed to reduce drag caused by a bent tusk (Kingsley & Ramsay 1988). A narwhal’s tusk grows from its left side, alongside a stunted right tusk, which only occasionally grows beyond a few centimetres (Graham et al., 2020).

The purpose of this massive tusk remains somewhat a mystery to this day, with theories ranging from an acoustic probe (Best, 1981) a sound transmission honing tool (Ford and Fisher, 1978), a thermal regulator for cooling the body after bouts of extreme exercise (Dow and Hollenberg, 1977), a spear for hunting or finding food (Bruemmer, 1993), a weapon for self-defense against predators (Freuchen, 1935), a tool used for breaking the ice (Tomlin, 1967), an implement for digging when foraging on the seafloor (Newman, 1971), to even resting on ice to keep a breathing hole open whilst sleeping (Porsild, 1918).

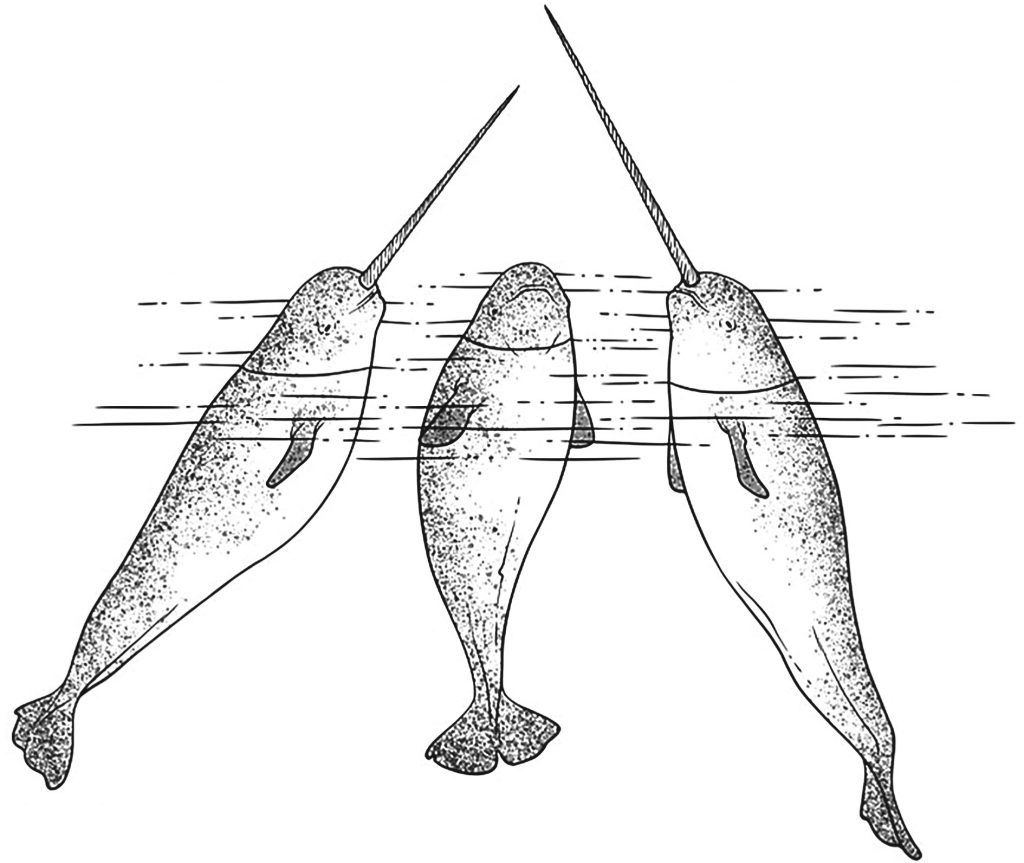

The theories listed above however, have largely been disproved or lack general approval in the scientific community. It is generally accepted now that the tusk’s primary function is during mating season to prove genetic viability to females. Given that the females do not have tusks, and have similar survival rates (actually living slightly longer on average) and diets (size restricted, males can be almost twice the size of females), it appears the tusks are not essential to survival (Graham et al., 2020). It has been difficult to prove the use of these tusks in narwhal on narwhal combat (similar to rutting deer), as the narwhal breed in thick pack ice making direct observations difficult (Graham et al., 2020). However male narwhal are almost always found to have scratch wounds around the base of their mighty tusk; with some even found with end pieces of other narwhal’s tusk embedded into their skulls (Gerson & Hickie 1985). While these sword fights are seldom observed, a similar display known as tusking is regularly observed, with males seemingly comparing tusk size usually in close view of a female (shown below). Given that the tusks seem to be used to display the health and strength of a male to females, it follows that males would also use this posturing to avoid entering into potentially deadly conflicts they could not win.

Recently another use of the tusk has emerged thanks to close analysis, primarily by dentists, rather than ecologists. These dentists showed first through examination, then through practical experimentation, that the tusk of a narwhal is used as a sensory organ (Nweeia et al., 2014). Water first flows through porous channels, eventually connecting up to so-called pupil nerves, which allow the narwhal to sense ambient salinity (Nweeia et al 2014). A valuable asset in the ever-changing ice fields of the arctic, where a whale cannot know where it’s next breathing hole may appear.

As the full extent of the power of a narwhal’s tusk is revealed, it has proved a valuable resource for scientists. Using the tusks of dead narwhal, a team of scientists from across the world has used the growth rings inside the tusk to help them track dietary changes through the years (Dietz et al., 2021). Used in tandem with stable isotope analysis, which allows insights into dietary patterns, this provides an incredible bank of data which spans a long period of time, making this method arguably more valuable than behavioural observations or stomach analysis for diet.

The narwhal were found to have incredible dietary flexibility, both between individuals and overtime however, one major pattern was apparent. Between 1962 (the oldest data available) and 1990, the narwhal had a diet which heavily relied on arctic cod, armhook squid and Greenland halibut, these species are known as sympagic, meaning they are generally associated with the sea ice. From 1990 onward the primary food sources for the narwhal shifted to polar cod, armhook squid and capelin, a more pelagic, or open ocean diet. This shift coincided with the breaking up of major ice sheets in the region as climate change drove a change in the polar ecosystem.

This study also examined changes in the mercury content of the narwhal’s diet through the years, which despite large variability between individuals, showed a consistent and constant accumulation in all studied individuals (Dietz et al., 2021). This increase was initially driven by the reliance on Greenland halibut, who are themselves predators and are known to have issues with high mercury contamination. Following the dietary shift in 1990 away from Greenland halibut and other sympagic creatures, the mercury accumulation levelled off. That is until around 2000, when the melting of the ice reached a tipping point, nutrient cycling was significantly altered and the bioavailability of mercury (mercury which can be incorporated into the food web) increased dramatically. This pattern of recent mercury incorporation has been mirrored in other arctic predators such as arctic fox (Bocharova et al., 2013); beluga (Loseto et al., 2008); and ringed seal (Gaden et al., 2009).

The importance of the polar ice caps has been known to scientists for decades, and with public pressure thanks to the brilliant work by people just like you, our loyal Sea Watch supporters, the preservation of this and other unique ecosystems across the world is being made a priority. Together we can stop narwhals drifting into mythos like their imaginary equestrian cousins.

Jay

Sea Watch Volunteer

Feature Blogger

Bibliography

Bruemmer, F., 1993. The narwhal. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Key Porter.

Freuchen P. 1935. Mammals. Part II. Field Notes and Biological Observations. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921–24, 2 (4–5):68–278.

Kingsley, M.C. and Ramsay, M.A., 1988. The spiral in the tusk of the narwhal. Arctic, pp.236-238.

Newman MA. 1971. Capturing Narwhals for the Vancouver Public Aquarium, 1970. Polar Rec 15:922–923

Porsild MP. 1918. On “Savssats”: a crowding of arctic animals at holes in the sea ice. The Geographical Review, Vol. VI, No. 3 (September).

Tomlin AG. 1967. Mammals of the U.S.S.R. Volume 9. Cetacea. Jerusalem: Israel Program for Scientific Translation