Sightings are important because they give us information about where and when particular species occur, from which we can identify important areas and habitats, as well as determine changes in their status and distribution. Such knowledge helps provide better informed conservation measures.

-

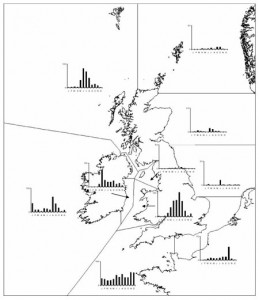

Sea Watch National Database More than two thousand people have contributed sightings to the national database that currently comprises over 60,000 records, making it one of the largest and longest-running sightings schemes in the world. Scientists and volutneers complete sightings forms for Sea Watch, recording not only the sightings they make but, where possible, also the number of hours spent watching or the distance travelled in a boat. Even when no cetaceans are seen, it is important to have a measure of effort in order to interpret sightings more effectively.

-

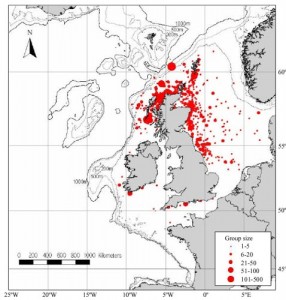

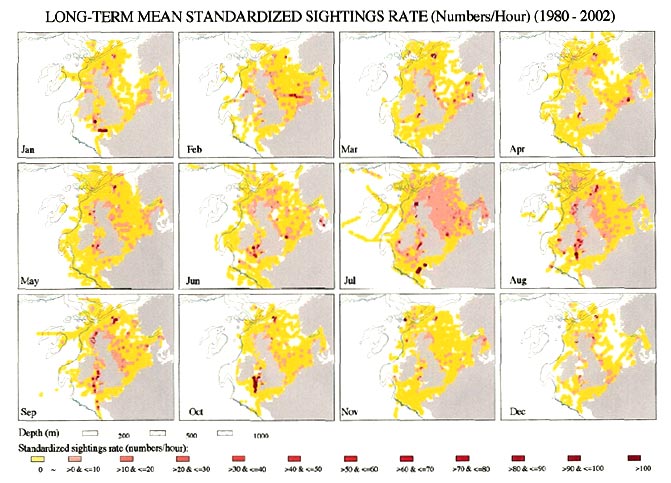

Identifying Critical Habitat and Establishing Protected Areas Taking these sightings records, and adding environmental data such as water depth, sea surface temperature, salinity, and measures of primary productivity, one can build up profiles of the habitat requirements of various cetacean populations and better understand the ways in which they are affected by their environment. This can enable us to identify potential hotspots for particular species so that recommendations can be made for where to establish Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) under the EU habitats and and Species Directive (see fig. 1 for an analysis undertaken for the statutory conservation agencies to determine whether SACs could be identified for the harbour porpoise).

Fig. 1. Harbour porpoise hotspots as derived from long-term mean standardized sightings rates using Joint Cetacean Database data collected between 1990 and 2002 (from Evans, P.G.H. and Wang J. 2002. Re-examination of Distribution Data for the Harbour Porpoise around Wales and the UK with a view to site selection for this species)

-

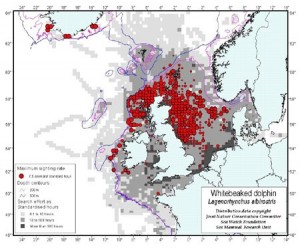

Distribution Maps The two images below show examples of the two main types of map that can be produced. Fig. 2. is a simple plot of sightings without associated effort, whereas Fig.3 links the sightings and effort databases with a geographical information system (GIS). In this instance, the latter is using data from a combination of databases, and therefore includes some information not included in Fig. 2.

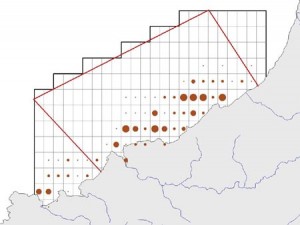

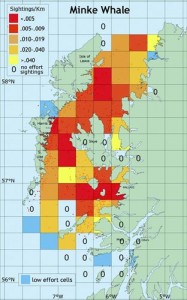

Fig 4. Distribution map of minke whales in Hebridean waters corrected for efrrot and sea state (from Boran, J.R., Evans, P.G.H and Rosen, M.J. (1999) Cetaceans of the Hebrides: seven years of surveys. European Research on Cetaceans – 13: 169-174)

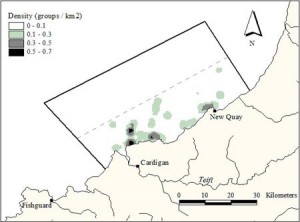

Maps can also be used on a finer scale at a regional level, in order to identify specific localities important for a particular species, and how these may vary seasonally or yearly. This sort of information is particularly useful for Environmental Impact Assessments prior to any human activity, like the building of a wind farm or harbour, a military exercise, or industrial activity like seismic exploration or pile driving. Fig. 4 spotlights important summer areas for the minke whale in West Scotland, whilst on an even larger scale, mathematical modelling of densities reveal hotspots in usage by bottlenose dolphins of the Cardigan Bay Special Area of Conservation (Fig. 5). By incorporating data, such as distance from coast and river mouths, we can build models to investigate the relative importance of these environmental factors. Figure 6, shows the output of a model used to predict the relative importance to bottlenose dolphins of different areas within the Cardigan Bay SAC.

-

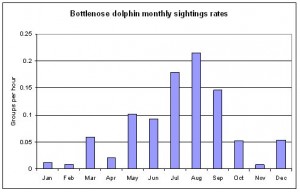

Seasonal Changes Cetaceans are generally very mobile, and for most species, numbers are likely to vary from month to month, particularly between winter and summer. Fig. 7a shows an example of variation in sightings rates for the short-beaked common dolphin between different regions of the UK. In the South-West Approaches to the Channel, southwards towards the Bay of Biscay, common dolphins are present in good numbers year-round, whereas off North-West Scotland, they are rare outside the summer months. These histograms, however, are uncorrected for effort and sightability due to variation in sea conditions. Although they may reflect the overall seasonal pattern in different regions, where possible, corrections should be made particularly for those two sources of bias. Fig. 7b shows monthly sightings rates of bottlenose dolphins in Welsh waters, corrected for effort, with numbers between October and March much lower than during the summer months. -

Longer-term Trends

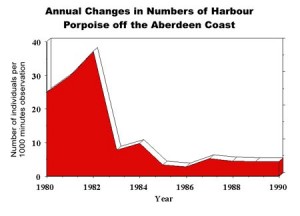

Fig. 8. Long-term changes in harbour porpoise relative abundance (corrected for effort) off the Aberdeenshire coast. 1980-90 (from Evans, P.G.H. 1992. Status Review of Cetaceans in British and Irish Waters).

Besides seasonal changes, systematic observations from both land and offshore can reveal longer-term trends in abundance of a species. Fig. 8 gives an example for the harbour porpoise from a regularly watched coastal site in Aberdeenshire. Although difficult to generalize using information from a single site, when a wider network of sites are providing information on a regular basis, it becomes possible to draw more general conclusions about status changes, bearing in mind that if those sites are all coastal, one is only seeing variation applying to that coastal zone. This is the reason why it is really important to also monitor populations further offshore, with survey vessels.

For further information about monitoring methods, see the following review paper:

Evans, P.G.H. and Hammond, P.S. 2004. Monitoring cetaceans in European Waters. Mammal Review, 34: 131-156.

-

Individual Photo-Identification

Fig. 9. Bottlenose dolphins showing unique dorsal fin markings that allow for individual identification.

Many animals have unique identifying marks, such as nicks and scars on the dorsal fin, colour variations, or pigmentation patterns on the back (Fig. 9). Over the last 20 years, photo-identification has become a standard technique to provide information on abundance, social structure, habitat use, ranging movements, and aspects of an individuals life history such as birth and death rates.

Sea Watch manages photo-identification catalogues of individual animals for a number of species (particularly bottlenose dolphin, Risso’s dolphin, killer whale, minke whale, fin whale, and humpback) as a national research resource. If you have any images of cetaceans that show individually recognisable markings, please do send them to us. All photos included in the catalogue will be credited accordingly, and we are happy to share our catalogues with other researchers.

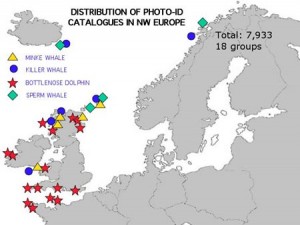

Fig. 10. Distribution of Photo-ID catalogues in North-West Europe contributing to the Europhlukes Project.

A recent EU funded project called Europhlukes, involved about fifty research groups all around Europe with the aim of establishing digital catalogues of images, along with computer-assisted matching procedures to facilitate the matching of pictures of particular individuals between regions. Other parties are invited to join Europhlukes (in its current phase, re-named Euroflukes) and to share their images and associated data so we can all better understand the ecology and movement patterns of a number of cetacean species (see Fig. 10). For further information about techniques for photo-identification, see the downloadable fact sheet on photo-ID.

-

Who are Sea Watch Observers The people who form part of the Sea Watch observer network go well beyond marine and fisheries biologists and include anyone whose work or leisure activities take him/her on or near the sea – fishermen, coastguards, ferry crews, weather ships, oil supply ships, oil rigs, holiday-makers, ornithologists, aircraft pilots, merchant and royal naval seamen amongst others. In this way, anybody, whatever their background can become directly involved, in a practical sense, with the conservation of marine wildlife in Britain and Ireland. -

How do Results Inform and Influence Conservation Measures The collation of information on abundance and distribution of whales, dolphins and porpoises is valuable in many ways. Besides increasing our general knowledge of the cetacean fauna that inhabits the seas around the British Isles, it can inform us of important areas and times of year for particular species, enabling better decision making on the risk of harm to local populations from certain human activities. It may also indicate where dedicated research should be directed, or draw attention to possible status changes on a local wider basis.The Sea Watch Foundation provides information on cetaceans to a variety of governmental and non-governmental organistions in the UK, including the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC; the Government’s advisers on nature conservation), the national statutory conservation agencies (English Nature, Countryside Council for Wales, and Scottish Natural Heritage), Environment Agency, Wildlife Trusts, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Marine Conservation Society, International Fund for Animal Welfare, RSPCA, Greenpeace UK, Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, Institute of Zoology, London Natural History Museum, and British Divers Marine Life Rescue, as well as to a wide spectrum of other users of the marine environment from recreation, commerce and industry.

Sea Watch, and its predecessor the Cetacea Group, contributed to the creation of the most important European Legislation to date for the protection of cetaceans – the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetacens in the Baltic and North Seas (ASCOBANS), and had input to the UK Wildlife and Countryside Act, EU Habitats and Species Directive, and UK Biodiversity Action Plan for Cetaceans. Sea Watch currently provides information for Environmental Impact Assessments (e.g. for harbour construction, wind farms, seismic activities), and offers briefs to the media publicising its work and informing on matters relating to cetacean conservation. Training aids, survey and monitoring methodologies, and computer software developed by Sea Watch are available for use worldwide. Cetacean Status Reviews using both casual and effort-related sightings data have been commissioned by the Nature Conservancy Council (2986), UK Department of the Environment (1992) and English Nature and Countryside Council for Wales (2003).

Sea Watch contributes to the Joint Cetacean Database (JCD), which is the amalgamation of three cetacean databases from the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) and Sea Watch Foundation (SWF). The JCD must be one of the largest of its type in the world and has been used in the production of the recently published European Cetacean Distribution Atlas (Reid, J.B., Evans, P.G.H. and Northridge, S.P. 2003 Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-West European Waters. Joint Nature Conseration Committee, Peterborough 76p.

Sea Watch staff currently participate in the following committees: ASCOBANS Advisory Committee, Europena Cetaceans Society Executive Council, Species Action Plans (SAP) Group for Cetaceans and Marine Turtles, Wildlife and Countryside Link Groups on Whaling and Fisheries, BBC Wildlife Advisory Panel, External Advisory Panel of Association of Oil and Gas Producers, and Advisory Panel of the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA).